Let's start with Inflation

The macroeconomy in 2021 prompted me to write on Substack. Mostly is was Inflation. Rather, others’ seeming confident understanding of the subject, relative to my own, is what prompted me.

I’ve been studying and teaching macroeconomics for two decades, give or take. Against that backdrop, I became intrigued by how self-assured those opining on inflation in 2021 seemed to be about it. This was curious to me since it had been my impression that over the past decade or so the subject of inflation had been a bit confounding to macroeconomists, especially those that focused on monetary policy and the Fed. The confoundment generally centered on the question of why had inflation been so low for so long?

“Hmmm, what am I missing?” I thought a few times over the past year. Why are others seemingly so sure, yet I am not? This Substack newsletter is my attempt to understand what the heck has been, and is, going on.

To preview, my hunch is we’re looking at an aggregate demand story. While the “supply chain” has been getting a lot of attention, and blame for recent inflation, I think the supply chain issue is a red herring. (For example, I disagree with the sentiment expressed in this article from MarketWatch, though I find the author’s viewpoint interesting.)

The answer is extremely important for how we think about what’s coming next for our economy. And, for how we think about macroeconomic policy—as in, “can the Fed do anything about inflation?” My claim is this: recent inflation is an aggregate demand issue, and, yes, the Fed can do something about it.

To begin, let’s take a look at recent history.

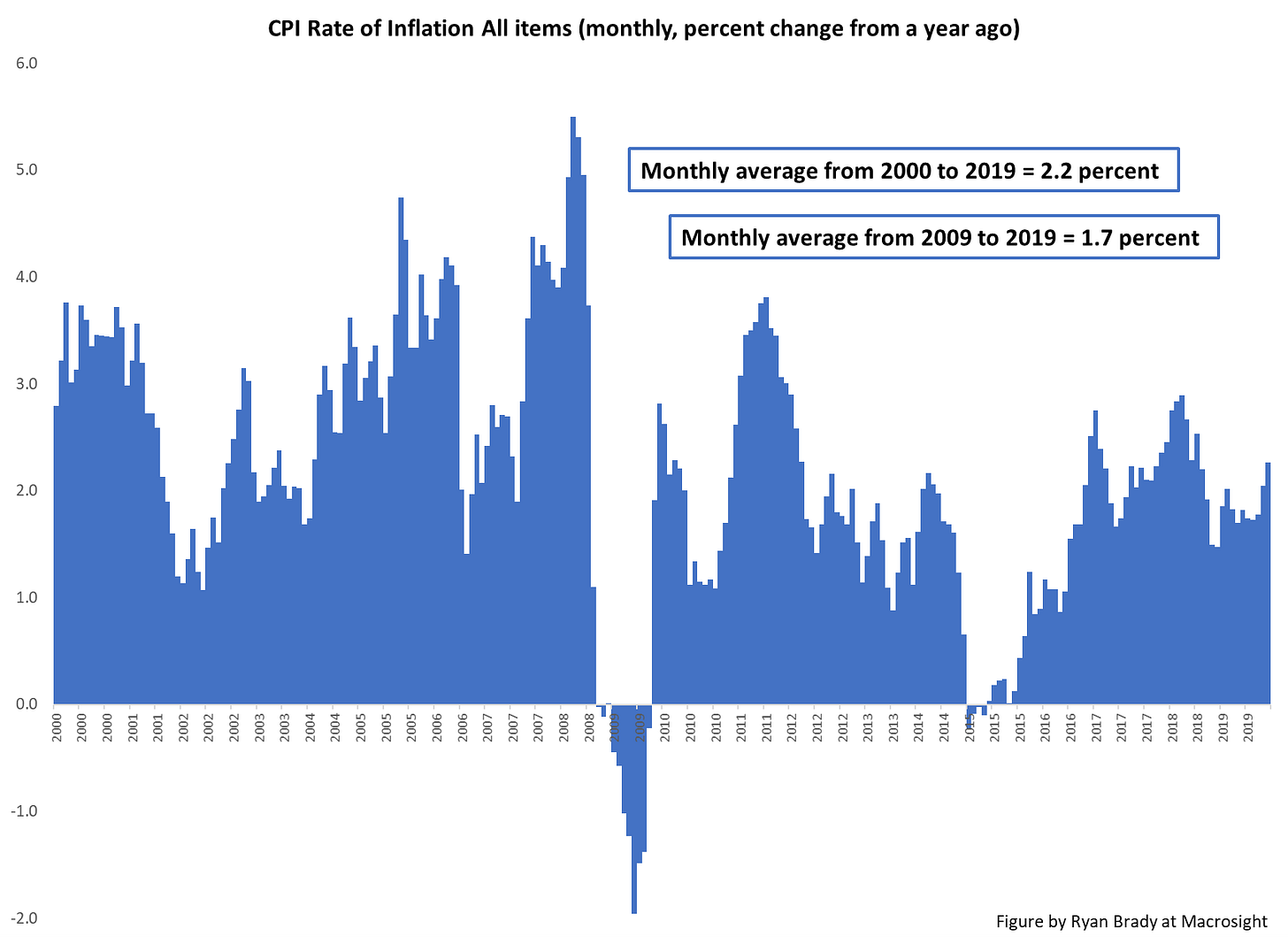

The CPI rate of inflation from 2000 through the end of 2019 averaged 2.2 percent per month (all items, monthly frequency, measured as the percent change from a year ago). From July 2009 (right after the end of the Great Recession) to the end of 2019 the average was 1.7 percent per month. Here’s a picture of it:

Over the same time spans, real GDP growth averaged 2.0 and 2.3 percent, respectively (I show a figure of GDP further down the post). While those GDP numbers were not blistering, it was at least considered curious why inflation was not stronger, especially since the period 2009 to 2019 marked the longest expansion in history (and given the Fed’s quantitative easy policies over that period—a topic we’ll touch on another time).

Okay. Well, then this happened with inflation:

Things took a turn in 2021, in other words. The most recent monthly reading as of this post is for December ’21 (though not captured in the figure), with the rate of inflation reading at 7.0 percent (on the heels of 6.9 percent in November).

How did this stack up against real GDP? Here’s real GDP since 2009:

While both the second and third quarter of 2021 dominate the picture, what interests me for our inflation story is the past year—the fourth quarter of 2020 through the end of 2021. In the figure above, the bars in red mark the first quarter of ’20 and beyond. The last bar, in purple, is the fourth quarter of 2021—highlighted in purple since this is an estimate, as of January 10th, 2022, from the Federal Bank of Atlanta’s “GDPNow” forecast (6.8 for the Q4 of ’21).

So, what am I taking away from this? Real GDP growth has been unusually strong since the fourth quarter of 2020—and by “unusual” I mean compared to the past twenty years. To me, based on my understanding of the macroeconomy, macroeconomic theory and all the time I’ve been thinking about those things, well . . . recent inflation makes sense. If real GDP growth is unusually high, then it makes sense to me that the rate of inflation is unusually high. The situation passes a very simple macroeconomic smell test, in my opinion.

All of this thus far, of course, is just a cursory examination. When you dive deeper into the numbers, the story gets more compelling. I’ll expound on this claim in my next post, where I focus on consumption spending—the largest component of real GDP.

Super interesting, Ryan. I wonder what you think about how the short run elasticity of supply factors into this. I wonder if inflationary outcomes would be different with a similar growth in GDP but mechanized primarily through a supply shock (if that’s a mechanism that can exist?). It seems to me that intuitively the short run elasticity of supply is quite inelastic, leading to the outcomes we’re seeing, but short run demand elasticity may be more elastic, which could have interesting implications for inflation. Luckily I can walk down the hallway and ask you in person! Thanks for sharing.