“Supply-chain problems” is a broad concept, and can refer to any number of things—transportation times, time to delivery of raw materials, waiting months for your new refrigerator, and so on. For most of us, supply-chain problems mean higher prices—at the grocery store, at the hardware store, and just about everywhere else. The supply chain, too, has been cast as the villain in our current national inflation nightmare, with some, arguably, misjudging its impact.

This narrative begs the question: how is the supply chain connected to inflation? Recall that typically when the news or economists refer to “inflation,” they mean the rate of increase in the prices of consumer goods and services. Yet, those goods are obviously made up of materials of some sort. Hence, a natural way to look for a connection between the rate of inflation of consumer goods and the supply chain is through producer price indexes. The latter track the prices that companies pay for the materials they use to make the stuff we want.

How changes in producer prices eventually feed into changes into the items we buy is known as “pass-through” by economists.

Pass-Through Prices

There are dozens and dozens of “producer price indexes” for just about every commodity and/or manufacturing input you can imagine. Just as they do with the CPI, the BLS produces these indices. A commonly cited index from the BLS is the “The Producer Price Index for final demand,” which is a comprehensive statistic that captures price changes for just about every input tracked by the BLS. Here’s the PPI for final demand since 2019:

First, you can see our recent experience emphasized in red—from May 2020 through June of 2022 we had 26 consecutive months of increases in the PPI. Notice also the annotations on the figure—the average over this period was 9.2 percent, which was three times the average for this price index from 2000 through 2019. Only in the last three months did we have any negative turn in the series. This recent experience is unusual for two reasons: the high rate of growth over a two-year period and the 26 consecutive months of increases.

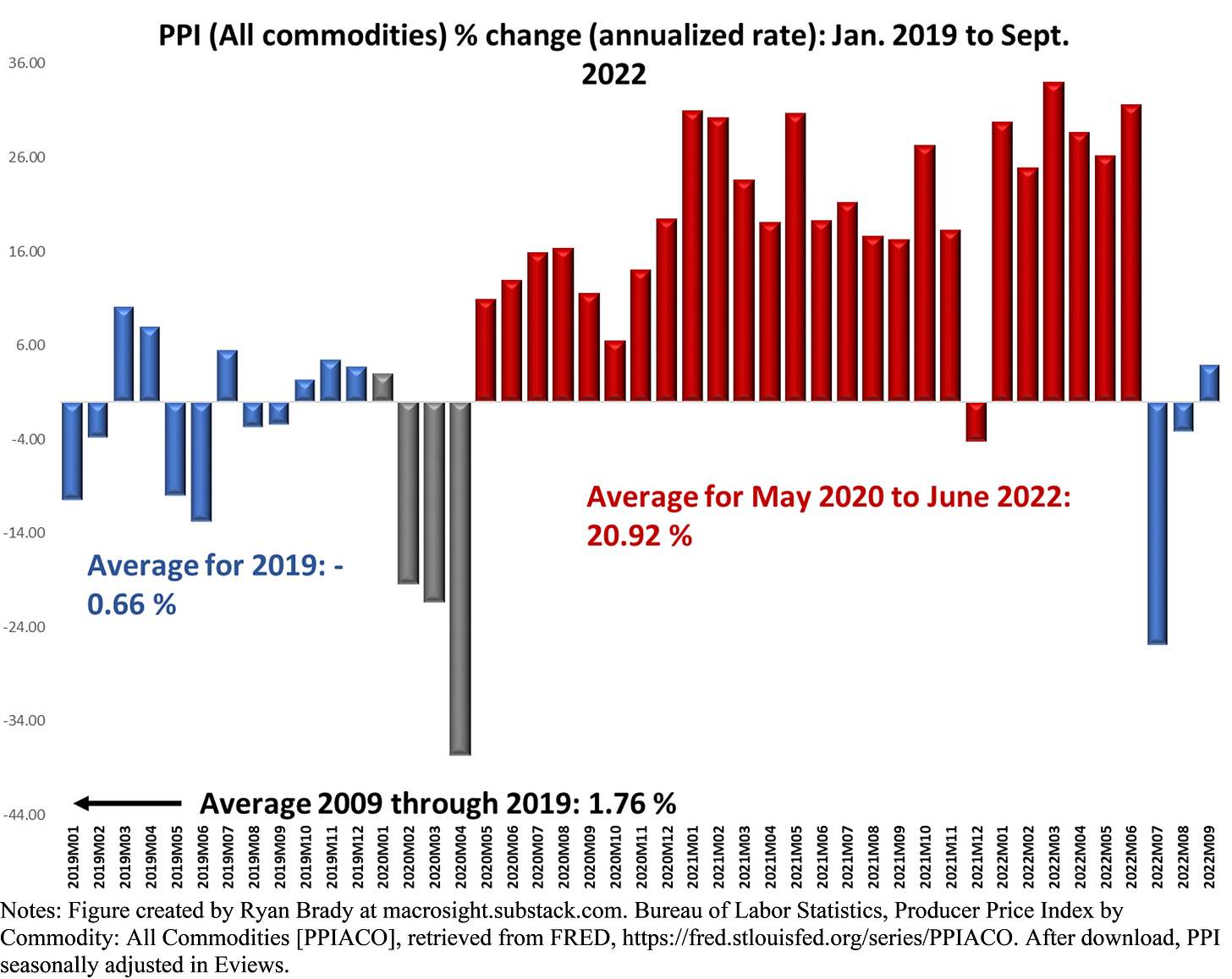

An alternative PPI index focuses on the price of commodities, the “Producer Price Index by Commodity: All Commodities.” Since 2019 this series looks as follows:

For this PPI index, we see a similar story: unusually high and sustained price increases month after month. In this case, there were 19 straight months of consecutive increases, then another six months. Compare this to our experience going back to 2000, as shown here:

With a cursory look you can see that producer prices are typically volatile, especially so from 2001 to 2007. While there were periods of sustained increases, those earlier periods were either not as long as what we have experience since May of 2020, or those sustained periods were followed by at least a few months of deflation of the producer price index.

Thankfully, in the past three months we have had two months of PPI deflation followed by a relatively mild increase of 4.3 percent for September. Yet, we need more deflationary periods for the PPI if we are to get back to “normal”—at least what was normal over the 2001 to 2019 period.

The PPI and the CPI

How will getting back to PPI “normal” matter for the inflation of consumer goods and services? Let’s see what the CPI rate of inflation has been doing:

The pattern of the CPI since 2019 is similar to the pattern of the PPI—mild inflation in 2019 and early-2020 (with Covid-induced deflation for three months), followed by high rates of inflation for 25 consecutive months.

We can get a sense of how the PPI and the CPI are related by looking at the correlations between the current values of the indices, as well as how past changes of the PPI correlate with today’s CPI rate of inflation. This is shown in Table 1:

Correlation reveals how variables move together over time (or in a sample). This table reveals that today’s inflation is highly correlated (at a value of 0.78) with today’s PPI value (remember that perfect positive correlation is a value of 1.00). And, today’s rate of CPI inflation is also correlated with the past few months of PPI inflation (at a diminishing rate, meaning the effect of a change in the PPI six months ago is less connected to today’s CPI than more recent months).

Note, it is always wise to remember that correlation does not imply causation. Instead, we can think of changes in the PPI “leading” changes in the CPI. As the price of inputs rise, producers tend to “pass-through” those increase to consumers, as competition and price elasticity of demand allows. The correlations in Table 1 are consistent with that notion.

A common thread

Clearly logistical problems from Covid-19, Covid-related shutdowns, and the war in Ukraine, among other factors, underlie what we see in the producer price indexes. Yet, while correlations can be compelling, and the correlations in Table 1 are consistent with pass-through, correlations are not proof of pass-through.

Moreover, it is too simple of a narrative to say that Covid-19 begat higher prices on raw materials, transportation, labor, etc., and all of that begat higher consumer prices.

We should not forget that a common factor has helped drive increases in the PPI and CPI at the same time. A historic increase in consumer spending is that common factor. Certainly, Covid-19-produced logistical problems would have pushed the PPI upwards, all else equal. But, without the ravenous pace of consumer spending—recall, the average month-to-month increase in 2021 was three times the rate experienced from 2000 to 2019—it seems unlikely the PPI, or the CPI, would have reached the high and persistent rates we see in the figures above.

That is, historic consumer demand has put pressure on the prices of goods and services to increase. That extraordinary pressure simultaneously put the already-strained supply chain under further strain as producers attempted to keep up with that demand. That extra supply-chain-strain further goosed producer price inflation, which has put even more pressure on the price of goods and services to increase, and so on, and so on.

What’s next for the Supply Chain?

As shown in the figures above, the PPI declined in July and August, and then was positive again in September. Also, the increase in September was relatively small. Does this recent pattern portend some positive news with respect to the supply chain and CPI inflation? To get a sense of that possibility we can look deeper into the PPI.

The BLS provides separate indexes for numerous sub-components of the broader PPI measures. There are dozens, in fact. For example, there is a PPI for lumber, a separate PPI for wood pulp, for semiconductor parts, for rubber, for paint, for industrial chemicals, and even for “hides, skins and leathers.” I collected 57 of such categories to get a sense of where the overall PPI might be heading. The figure below shows the month-to-month percentage change for all those categories from July, August and September.

What can we take away from this figure? First, in the last couple of months about half of the series declined, while about half increased. Second, September appeared to be the “calmest” from a volatility perspective. To getter a better sense of things, compare the last three months to the first six months of 2022, shown here:

Notice in both figures, the vertical axis maximum and minimum are the same. Clearly, the first six months were more volatile than the past three, especially in the positive direction. Visually it is difficult to make out the frequency of the positive changes versus the negative changes; however, I tallied up those frequencies for each month, which are shown in Table 2.

These frequencies provide a glimmer of hope. The last two months have provided the highest number of negative-change producer price sub-categories. Both values of 25 and 23 for the past two months, respectively, are more than double the typical value for the first five months of this year.

Do two months constitute a new trend for supply-chain prices? Not necessarily. But hopefully we are headed in the right direction and we will see the PPI continue to come down from recent historic highs. If the PPI-CPI correlations are any guide, the CPI should follow suit, at least to some degree.