On the first day of my forecasting course, I enjoy telling my students that if they learn anything about forecasting by the end of the semester, it will be to not trust forecasts.

Of course, I’m saying this with “tongue in cheek” to get their attention. But, there are truths behind the quip—a truth I clarify as the course unfolds. The primary truth being that forecasting our macroeconomy is very, very difficult. Even the most practiced and experienced forecaster can only provide so much guidance.

No one—or entity—knows such a truth better than the Federal Reserve. In fact, I suspect there is no greater collection of forecasting brainpower found anywhere in the world than at the Federal Reserve.

You see, in addition to the main headquarters found in Washington D.C. (the “Board of Governors”), there are twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks scattered around the country. And like the headquarters in D.C., each regional bank is staffed with dozens of PhD economists all working to understand the macroeconomy. Collectively I’m not sure you could find another employer with that many econ-nerds all working towards that end. And while not all of those PhDs are tasked with forecasting, there are a lot that are, all aided by countless research assistants, stats-geeks, data-dorks, and the like. If anyone knows forecasting, it’s the Fed.

Fortunately, as part of their mandate to set monetary policy, the Fed publishes the culmination of that collective forecasting effort four times a year. They do so as part of the meetings of the “Federal Open Market Committee” (the FOMC). Documents for each meeting are available here (the FOMC meets more than four times a year, but only publishes forecasts at four of those meetings). A full example of their forecast report—the latest one from last month—is found here.

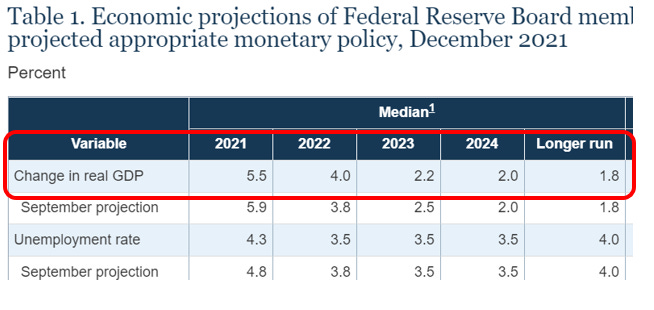

Let’s focus on the main part of that report for a second, cut from the December 2021 report and pasted below.

As you can see, the report provides forecasts for the “big three” macro variables—real GDP, the unemployment rate and inflation (measured by the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator, the price index the Fed prefers to focus on instead of the CPI). The report also provides the expected “path” of the Federal Funds rate—the interest rate the Fed uses as a lever, or as a signal, to manipulate economic behavior in the macroeconomy. The report also shows the forecasts for each variable and each time period from the previous meeting (in this case, September 2021—you can find previous forecasts online going back to 2017; you have to dig further in the various published information to find them going back farther).

For the econ/data nerd there is a lot of interesting stuff in this one table. For now, however, let’s focus on GDP (we’ll focus on the PCE and the unemployment rate in future posts; for example, notice the Fed thinks inflation will fall below 3.0 by the end of 2022!!!).

The first thing to notice in the snippet above is the forecasted path of real GDP over the next few years. The 5.5 percent for 2021 is probably going to end up being close to the actual value for 2021—recall this estimate was made just a couple weeks from the end of 2021.

For 2022 through 2024 the Fed is predicting a decline from 4 to 2 percent. And, the decline appears to be converging to the “Longer run” estimate of 1.8 percent. These forecasts raise a few questions.

1. Why is the Fed forecasting a decline?

2. Why does the decline fall from 4.0 to 2.2 (a change of 1.8), and then from 2.2 to 2.0 (a change of only 0.2).

3. Why these numbers? (Why not 5.0 for 2024, 4.0 for 2023 and so on?)

4. And, perhaps, most intriguing, why 1.8 percent for the “longer run”?

Let’s take the last question first. Take a look at the growth rate of real GDP going back to 2000, with the Fed forecasts added to the graph.

As displayed on the figure, the average quarterly growth rate since 2000 has been 1.95 percent; and only a little higher if you end the sample period with 2019. Hmm . . . okay, so maybe the Fed is extrapolating in some way from that 1.95 estimate, but downwards a bit to 1.8 percent. Let’s come back to that.

How about the forecasted rates for 2002 and beyond? Well, what is going on here is the Fed is forecasting that the U.S economy is going to come down from recent “highs”. Recall from my discussion in an earlier post (Let’s start with Inflation), real GDP has been running hot since the second half of 2020. For example, from the fourth quarter of 2020 through the end of 2021, the average growth rate was 5.2 percent—more than twice the historical average since 2000.

What we are observing in the Fed’s forecasts are two important truths of forecasting variables like the growth rate of GDP.

One, the long run historical average is the best information we have for forecasting out to the “longer run”—meaning beyond just a few future time periods.

Here, I’m comparing the historical average of 1.95 to 1.8 only because I haven’t guessed yet the form of the forecasting model the Fed is using to generate the 1.8 prediction. Moreover, the 1.95 percent is a simple or “unconditional” average. The 1.8 percent the Fed is reporting is (likely) a “conditional” average, meaning it’s been estimated from a forecasting model (where the estimate is “conditioned” on various factors included in the model). Also, I’m using 2000 as the start of the “historical” time frame in the figure above—the Fed may be using a longer period, or shorter.

Two, given the long run average, if the variable has been unusually high or low relative to that average, the best forecast is for a convergence—in the next few periods—back to that long run average.

The reason for this is that the unusually high or low periods represent some deviation (driven by some unusual event like, ahem, Covid-19) from the long run average. The effect of that unusual event on the variable will eventually “wear out,” and the growth rate will converge back to that long run value.

(This is the case when a growth rate of a variable is defined as “mean-reverting”—a statistical property of many variables that evolve over time—but not all.)

That explains question number 1 above. We’ve been above average, so it stands to reason the Fed thinks that we are going to fall back to it soon. Moreover, since the Fed intends to raise the short-term rate, as shown in the published table above, they are likely building in their own expectation on how that increase in rates will affect GDP growth.

That leaves us questions 2 and 3 above—why those numbers for 2022, 2023 and 2024? Recall the numbers in the table represent an average of the various forecasts from within the Fed. The numbers we see are a function of the specific forecasting models used by various researchers, and the time period over which those models were estimated.

To try to “hack” the gist of the forecasting approach by the Fed, I ran my own forecast model for real GDP growth. I used a standard (and simple) model in the world of forecasting. However, I couldn’t quite replicate their values. The closest I came was as follows:

(I won’t bore the reader with further details on that exercise. But, for the those inclined I provide some details at the end as a postscript, in “Nerd Corner.”)

Of course, I didn’t expect to “stick the landing” exactly, so maybe my estimates are not too bad. Either way, I think we’ve effectively answered, at least in part, the four questions the Fed forecasts raised. The Fed is forecasting that what has gone up (above the long run average), must come down (back to that long run average). The exact path of that process—4.0 to 1.8—is a function of their internal models.

Lastly, I leave you with one last intriguing insight about forecasting the macroeconomy, which comes, of course, from the Fed. In the table below, I’ve recorded the “longer run” forecast number the Fed has reported in each published forecast going back to late 2015.

Since late 2016, you can see the “longer run” forecast has bounced between 1.9 and 1.8 percent. And, remarkably, the longer run forecast has dropped only a tenth of a point since the onset of the Covid-19 era (or 10 “basis points” as finance nerds like to say). As far as the stability of the macroeconomy is concerned, in the long run, Covid-19 barely registers a blip. Intriguing, indeed.

So, for those of you out there working in the private sector, what are you expecting for the macroeconomy and what that means for your particular business or industry? Does your expectation for GDP in 2022 and beyond match the Fed? Are you more pessimistic or optimistic?

If you are unsure, then a place to start is with these Fed forecasts. Know what the Fed knows, and then proceed accordingly.

Postscript: Nerd Corner

In a quick attempt to replicate the Fed’s numbers, I estimated real GDP growth as an autoregressive model of order one—AR(1)—with intercept. I did so with annual GDP data from 1984 to 2021—a relatively small sample, yes; but I did not want to go back further in time (I used 1983 as a “break date” given research on the “Great Moderation” that started around then). I went with annual data since you get persistence (the parameter on the lag of GDP is positive and statistically significant). The partial autocorrelation coefficient was 0.27 (statistically significant at the 10 percent level) and the intercept was 1.92. Those parameters generated the forecasted values I cite above as “My forecasts”.

I played around with different possible values for the parameters in the AR(1) model, but what I cite above is as close as I got to replicating the Fed. Of course, I chose the simplest (arguably) forecasting model possible. This suggests the Fed researchers are doing something more elaborate, with many different forecasting models coming into play. That is not surprising, of course.