King Hippo

Long may the American Consumer reign

In the first few days of an introduction to economics course you are likely to hear the term “Consumer Sovereignty.” Consumer Sovereignty means that in a market economy, all economic activity is driven by the consumer. If you want to succeed in business, give the consumer what they want. If you want to really succeed in business, give the consumer what they don’t know what they want. And then they’ll buy a ton of it. The American Consumer is a Hungry Beast, like a Hippo, maybe.

At the macroeconomic level, consumer sovereignty is exemplified in the GDP share statistics. For the U.S. economy, about two-thirds of production is devoted to satisfying the needs, wants, and cravings of the consumer today. I showed a graphic of this in a previous post. Another 18 or so percent of GDP is devoted to investment spending, which is the process of providing consumption to the American consumer tomorrow. Government spending makes up most of the rest, which—in theory—provides the consumer things the market doesn’t provide enough of, like national defense and infrastructure.1 In short, the majority of economic activity revolves around the American consumer. Consumer sovereignty drives everything, and perhaps King Hippo is a fitting regnal name.

“Ha Ha Ha! I'm the King!”

If the consumer is King, what does that mean for our economy in the next few months? With inflation at the forefront of consumers’ thoughts, many are predicting or suggesting that consumer spending will surely fall as the economy tumbles into a recession. On the one had, after a crazy 2021, it is logical to expect consumer spending to slow down in 2022, recession or no recession. However, if consumers become fearful of a recession, then consumer spending may fall even further. In such a scenario, a recession or near-recession gets worse, consumer spending falls even further, and the economy spirals further in the wrong direction.

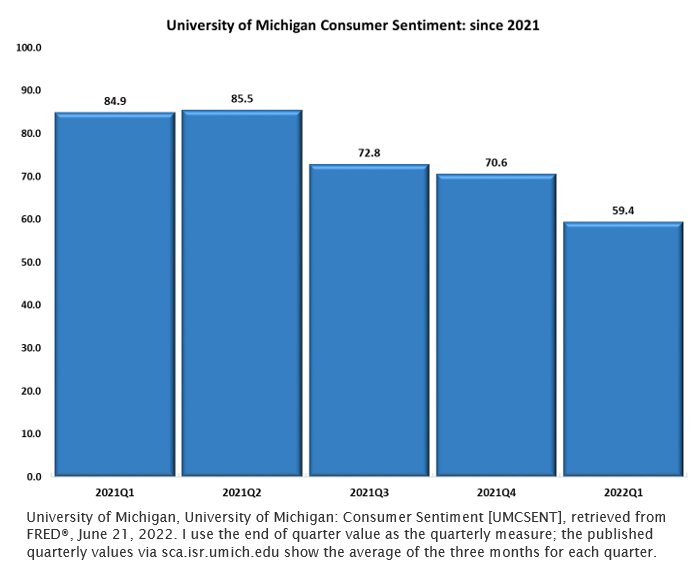

Not surprisingly, consumers’ feelings are making headlines, and things are not looking good. The University of Michigan (UMICH) publishes the Index of Consumer Sentiment via their Survey of Consumers (previously mentioned here). Check out the quarterly measure of sentiment since the beginning of 2021:

It is obvious King Hippo is not in a good place. UMICH’s sentiment index hasn’t fallen below a reading of 60 since 2011.

So, how can we use this information to predict what might be coming, with respect to the severity of any forthcoming recession? The sentiment readings may tell us something about future consumption.

“I feel like eating after I win”

First, let’s consider how important consumption spending is to real GDP growth each quarter. The relative importance of consumption is captured by a statistic produced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis called “Contributions to Percent Change in Real Gross Domestic Product”(downloadable here). With respect to consumption the “contribution” of consumption spending reveals how much GDP would have changed if consumption had not changed at all. In that way, we can see how important consumption was to that quarter’s GDP statistic (as explained by the BEA here). The relative importance of consumption is captured in this figure:

The graphic implies the following: if consumption had not changed at all during the first quarter of this year, real GDP would have fallen by 2.1 percent more than it actually did. Or, if you look back to the first two quarters of 2021, real GDP growth would have been negative in both quarters, if not for consumption.

Consumption is King, indeed. Yet, it is not a lock-step relationship. For the second half of 2021 real GDP growth would have been positive regardless of consumption (at 1.0 and 5.1 percent for the third and fourth quarter, respectively). But, consumption certainly helped pump those numbers up!

“I have my weakness. But I won't tell you!”

To gauge the possible impact of King Hippo’s current mood, we can do some statistical analysis.

To do so, I analyzed data on consumption and its components (services, durables, and nondurables) along with the sentiment index. Let’s start with a simple metric, the correlation between the variables.

Table 1 displays the correlation coefficients between the consumption variables and the sentiment index. The consumption variables are measured as period-to-period percent changes. For sentiment, I consider the index in its published form (i.e., 84.9, 85.5, and so on, as shown in the figure above), along with two different “versions” of that index, the first difference and the rate of change. I will explain a bit later why I considered three versions of the sentiment index. First let’s look at the results.

A correlation coefficient, as shown in Table 1, provides a measure of how two variables “move” or change together over a sample. In our case, the sample is a period of time (the second quarter of 2002 through the first quarter of 2022). For example, the correlation of 0.20 between total consumption and the period-to-period difference of sentiment, reveals a positive but not-so-strong correlation over the twenty-year period. A very strong positive correlation would be closer to 1 (a rule-of-thumb is that a correlation of around 0.70 and higher is “strong”).

What is the purpose of considering three different versions of the sentiment index? If the sentiment index is going to tell us something about consumption growth, we need to speculate on what sort of information the index is revealing about consumers. Does the most recent value of 59.4 tell us all that we need? Or does the decline in every period since the beginning of 2001 reveal something important? Or, is it the rate at which that decline has occurred that portends doom for consumer spending? This may seem like splitting hairs, but such details are important in statistical analysis.2

However, regardless of the version of the sentiment index, the correlations shown in Table 1 are relatively low. The highest correlation—between the sentiment index values and nondurables—is only 0.26. The results suggest a mild to lukewarm relationship between what King Hippo is feeling versus what King Hippo is actually doing. The feeling and doing are obviously related, but these correlations suggest the feeling and doing may not be as related as one might think.

Yet, these correlations show only a coincident relationship between the variables. For any sort of forecast, we want to know how a change in sentiment now matters for consumption tomorrow. For that, we need something more detailed than correlation analysis. Since this post is already long enough, I am going to focus on those details in my next post.

The last part “net exports” (exports minus imports), is the difference between what foreign consumers buy from the U.S. versus what the American consumer buys from other countries.

The version of the variable matters when calculating a correlation. A correlation statistic is based on the idea that within a sample, each variable fluctuates around its average value in that sample. Therefore, the computed correlation statistic will depend on the specific units of the variables. For example, the “difference” is the simple change in the value between periods. Referring to the figure shown earlier, the difference between the first quarter of 2022 and the last quarter of 2021 equals a negative 11.2 (calculated as 70.6 – 59.4). The growth rate is the rate of change between periods. The growth rate between these two quarters is a negative 16 percent (calculated using the simple growth rate formula of ((new – old/old)*100).