Nominal & Real GDP

Same, but different

It’s been a busy week for many—kids back to school, fantasy football drafts taking place, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) dropping some important macroeconomic data. Today, for example, the BEA reported the July estimates for consumer spending and personal income, each statistic revealing the American consumer remains, at least for now, steady.

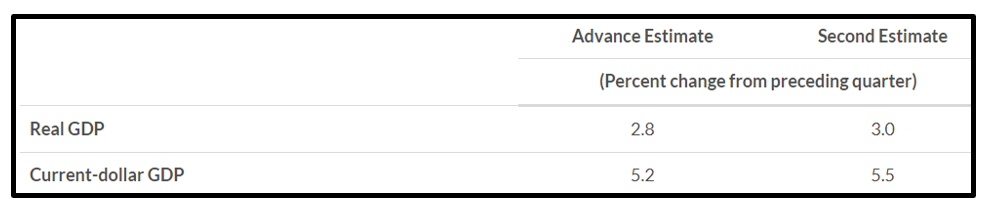

Also, yesterday the BEA reported its “second estimate” for GDP from the second quarter of this year. As seen in the snippet from that report below, both Real GDP and Nominal GDP—or “current-dollar GDP”—were revised slightly upward (from the initial or “advance” estimate).

Since, like many students and teachers out there, Macrosight finds himself back in the classroom teaching Macro 101, the BEA’s release was a welcome dash of updated data with which to bore my students. In line with my classroom discussion this week, let’s break down the difference between “real” GDP and “current-dollar” GDP, or as we call it in Macro 101, “nominal” GDP.

Nominal & Real GDP

Earlier this year, Macrosight explained definition of GDP, which included the difference between measuring the “value of all, new and final goods and services” in current or constant prices. Measuring (or valuing) GDP in current prices is the intuitive strategy of counting up the number of all the goods and services produced in a year and multiplying those items by their prices in that current year. Measuring GDP in constant prices is the practice of converting current year values to constant or “fixed” prices.

In the latter strategy, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) chooses one year—called the reference, benchmark, or base year—to represent all years and then values all years’ goods and services at the prices that existed in the reference year (currently, for example, 2017 is the reference year for “constant” prices). Simply put, the BEA will pretend as if a car produced in 1960 cost whatever a similar car sold for in 2017.

That procedure gives us the estimate for real GDP, defined as,

Real GDP: Aggregate value of all new and final goods and services produced within a country over a specific period of time, measured at constant prices.

Nominal GDP, therefore, is defined as,

Nominal GDP: Aggregate value of all new and final goods and services produced within a country over a specific period of time, measured at current prices.

Figure 1 displays both nominal and real GDP for the United States from 1947 through the fourth quarter of 2023. Real GDP for each year is measured in 2017 prices while, as stated, Nominal GDP is measured in current prices at each point in time.

Notice first the annotation pointing out that in 2017 the value of real GDP and nominal GDP are equal. That is due to the fact that 2017 serves as the reference year for anchoring prices in time. As we go forward from 2017, average prices get higher and higher, hence nominal GDP is larger than real GDP ($28 trillion for the former at the end of 2023 versus $23 trillion for the latter).

Since prices are higher after 2017, the values of nominal GDP are “deflated” to produce the real GDP values. As we go backwards in time from 2017, you can think of the values of real GDP as being “inflated” from the nominal values, and real GDP (the red line) is higher than nominal GDP (the blue line). This is because in the past the average prices of goods and services were lower than what they equaled in 2017.

The Growth of Nominal and Real GDP

Isolating real GDP from Nominal GDP is useful since it allows us to focus on the number of things our economy is producing every year, independent of whatever the prices of those things may be. If we define our standard of living by the amount of goods and services our economy produces, then real GDP provides us the true measure of that standard of living. Nominal GDP clouds the picture since it includes both changes in the quantity of stuff as well as the price of that stuff.

Consider, for example, the dollar-values of both Nominal and Real GDP for the third and fourth quarter of 2023, displayed in Table 1.

Let’s calculate the growth rate of each from the third quarter to the fourth quarter. We do so as follows:

Note the difference—nominal GDP grew 1.4 percent from the third to the fourth quarter, while real GDP grew by 0.9 percent. Why the difference? Because the prices of goods and services changed. Since Nominal GDP is measured in current prices, and prices change from quarter to quarter, that change is “embedded” in the Nominal GDP number. In contrast, Real GDP is measured in constant prices; hence, the only that that changes with Real GDP is the quantity of stuff our economy is producing from quarter-to-quarter.

GDP and Prices

Nominal GDP and Real GDP both reveal important information on our macroeconomy. The former captures both the quantity of things and the prices of things. The latter focuses on the quantity of things. Both statistics provide a measure of the size of our economy, and how that size is changing, they just do so in slightly different ways.

Having both statistics, too, makes it easy to isolate how the prices of things are changing. That isolation leads to a price index known as the “GDP Deflator.” But, like I infer from the drooping eyelids of my students, I assume you’ve read enough for now. Macrosight will dive into the GDP Deflator in a future post.