Two related things occurred this past week for Macrosight.

In my macro 101 course, we finished off the semester discussing U.S. net exports and exchange rates.

Multiple family members attended one of the last Taylor Swift concerts (of her recent tour), which took place in Canada. Said family members are U.S. citizens and traveled from the U.S. to Canada for the event.

The latter provided a timely example for the former.

While the “Swiftnomics” of the Taylor Swift global tour has received plenty of attention (see these examples), less has been said about how the Swift events matter specifically for U.S. Net Exports or exchange rates.1

What a perfect opportunity for my macro 101 class and this blog!

How Did It End? As a U.S. Export

There are multiple implications for calculating U.S. GDP when a U.S. performing artist holds a show in a foreign country. The first thing to note is that as a U.S. citizen performing in a foreign country Taylor Swift is providing a service. That service is counted in U.S. exports.

Recall from this Macrosight post that the category of “U.S. Exports” in the National Income and Product Accounts includes the goods and services produced by U.S. businesses, on U.S. soil, and sold to non-U.S. residents. The “on U.S. soil” is crucial for the export of goods, but for services, the definition also allows for those services to be provided in another country.2

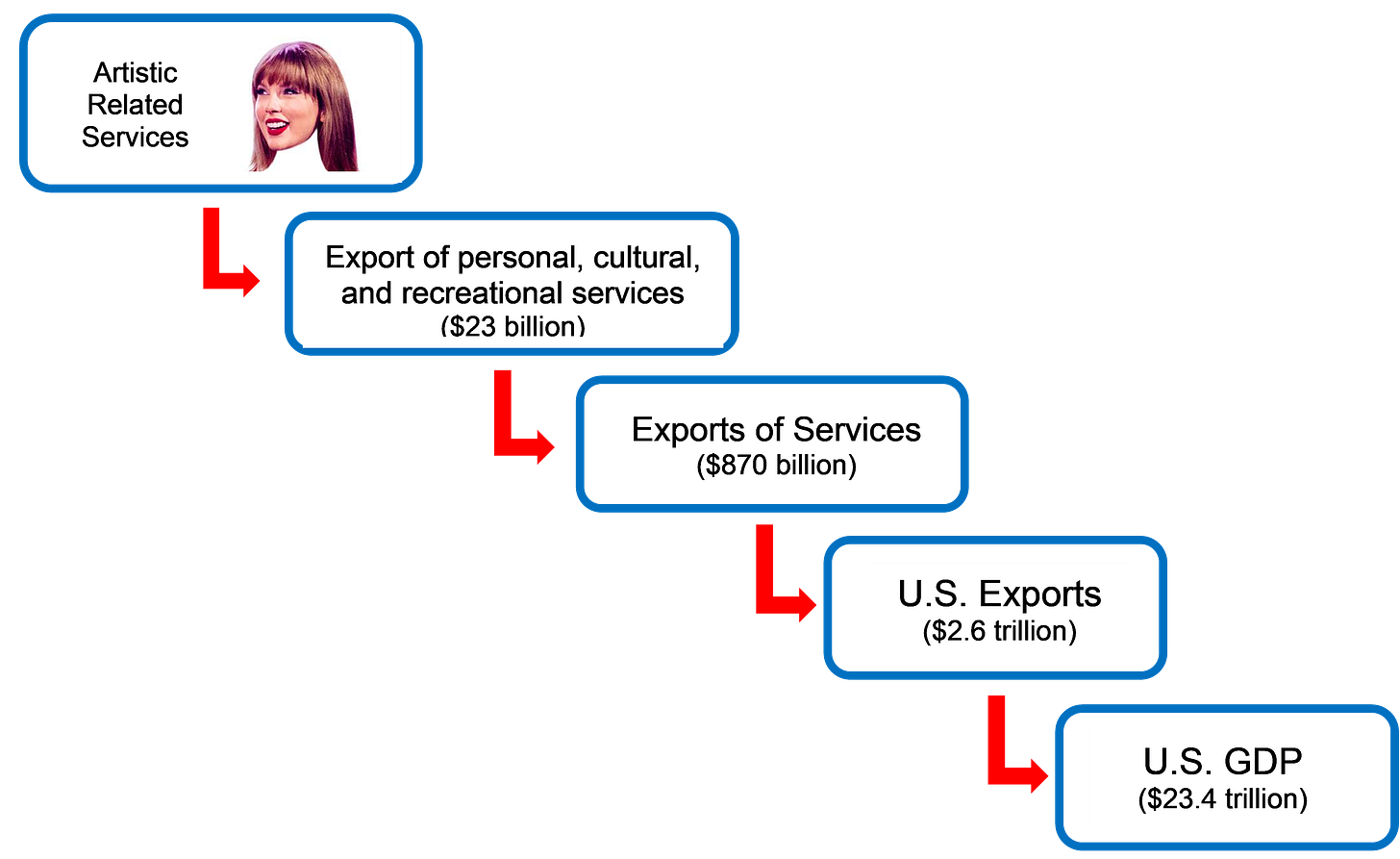

Within the total U.S. Export category as defined by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) is the sub-category, “Export of Services,” which then includes the sub-sub-category of “Export of personal, cultural, and recreational services.” And within that is yet another sub-category labeled “artistic related services,” which is where a U.S. singer’s concert on foreign soil gets counted.

That sequence of export-related categories can be visualized as follows:

(Dollar values shown are for the 3rd quarter of 2024; data are seasonally adjusted and adjusted for inflation (2017 constant dollars).3)

Artistic-related services “include fees paid to performers, athletes, directors, and producers involved with live events, such as concerts, theatrical and musical productions, and sporting events”(as defined and explained by the BEA here).

Unfortunately, I cannot identify in the BEA data the exact amount of “artistic-related services.” The closest we can get is to observe the category of which artistic-related services is a part, “export of personal, cultural, and recreational services.” This sub-category of total U.S. exports totaled $23 billion in the 3rd quarter of this year.4

You Belong with U.S. Imports

In addition to the export categories shown in the graphic above, there is additional spending related to any global performance by a U.S. entertainer. Anyone that has attended a concert or sporting event knows that there is a bevy of commerce occurring. There is food and beverage expenditure; merchandise sales within the venue; food, beverage and merchandise in restaurants and stores surrounding the venue; in addition to hotel rooms and travel to the event.

With respect to GDP, how does Macrosight’s family’s attendance of the Swift-in-Canada concert get counted? For example, how do we count the visit to Canada? Or the purchase of the concert ticket?

That answer is that any of my family’s expenditure while in Canada attending the Taylor Swift concert gets counted as a U.S. import (defined in this previous post).

When a U.S. citizen travels to a foreign country for recreational purposes, they are visiting as a tourist. As such, the money spent related to that trip is considered a U.S. Import—under the BEA-sub-headings of “Import of Services → Travel → Personal → Other Personal Travel.”5

The “Travel” category is explained by the BEA as follows: “

“Travel consists of transactions involving goods and services acquired by nonresidents while visiting another country. . . Travel . . . covers a variety of goods and services, primarily lodging, meals, transportation in the country of travel, entertainment, and gifts.”6

Hence, all the food and beverage purchased by my family members while in Canada is counted under U.S. imports. That is the same for any merchandise purchased while in Canada and for any hotel stays. When you, as a U.S. citizen, are in another country as a tourist (for any reason, attending a concert or otherwise), you are importing foreign products and services.

Notice also in the definition above that “entertainment” is included as part of “travel.” Hence, the concert tickets purchased by Macrosight’s family members are an import expenditure. This is a little confusing since the revenue generated by the concert, as noted above, is counted as a U.S. export. Yet, the particular transaction involving the American tourist attending the concert is technically an import.

Miss Americana and the U.S. Dollar

Finally, what effect, if any, did Americans’ trip to Canada for the Taylor Swift concert have on the Canadian-to-U.S.-dollar exchange rate?

The Canadian-to-U.S.-dollar exchange rate reveals how much one U.S. dollar is worth in terms of Canadian dollars, or vice versa.7 In my macro 101 class, I define this ratio as follows:8

As of the writing of this post, that ratio equaled about 1.44. That means if you are holding one U.S. dollar, you can trade that for one dollar and 44 cents in Canadian currency.

How could the Taylor Swift concert effect that exchange rate? When Americans travel to Canada, they need to give up U.S. dollars to get Canadian dollars. Hence, the demand for Canadian dollars increases relative to the U.S. dollar. In theory, therefore, the Canadian dollar will appreciate (become more valuable) relative to the U.S. dollar (all other factors held constant).

In that case, the ratio as written above would decline. For example, say that the ratio fell from 1.44 to 1.04. That implies the holder of one U.S. dollar receives less Canadian money in exchange for that U.S. dollar (40 cents less). Another way of saying that is the U.S. dollar has become less valuable relative to the Canadian dollar while the Canadian dollar has become more valuable relative to the dollar.9 That change in relative value is due to the fact that Americans are buying Canadian products (some Taylor-inspired bracelets for the kids, and bottles of Labatts for the moms and dads).

In practice, however, the fact that a number of Americans traveled to Canada for the concert probably did not “move the needle” much on the Canadian-dollar-to-U.S.-dollar exchange rate. Considering that Canada is one of the U.S.’s top trading partners, the amount of currency exchange for such a singular event is not likely to be large enough to affect the exchange rate that much.

Look what you made me do

So, as it turns out, Taylor Swift really has been everywhere, finding her way into the National Income and Product Accounts, my Macro 101 class, and even here in this blog.

Most articles on the Swift tour focus on the revenue earned, jobs created and so on. I could not find any (thought I really didn’t look that hard) that focused on the macro 101 angle: how the tour impacted the GDP statistics as computed by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, or (possibly) exchange rates. I’m guessing most outlets have not focused on those macro 101 topics since they actually want people to read their articles.

As defined by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, exports include “all goods and services sold, given away, or otherwise transferred by residents of the United States to foreign residents (also referred to as nonresidents or the rest of the world).” See chapter 8 of the NIPA handbook for more details (https://www.bea.gov/resources/methodologies/nipa-handbook/pdf/chapter-08.pdf). The bolded part emphasizes how to think about a U.S. performer “exporting” their services while performing abroad.

Source of data: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 4.2.6B. Real Exports and Imports of Goods and Services by Type of Product, Chained Dollars. Downloaded from bea.gov. Data is seasonally adjusted and shown in constant dollars (adjusted for inflation).)

The BEA does not publish the exact number for “artistic services”(at least that number is not publicly available that I could find). Also, since I am relying on BEA-published data for this post, I cannot say what Taylor Swift’s international concerts contributed to that $23 billion for the most recent quarter of 2024. However, the multitude of articles commenting on “Swiftnomics” provide a dizzying array of facts and figures (for examples, see the links provided earlier in this post). I should add, too, that my description is the simplest way of thinking about the GDP accounting in this case—a Canadian entity paying Taylor Swift directly. In truth there are likely a number of promotion and production companies through which the various payments are flowing. I am indebted to an official at the BEA for discussion on this, via an email exchange.

Airfare is counted under the services category labeled “Transport,” which is separate from the “Travel” category. Both “Travel” and “Transport” fall under the more general “Exports of Services.” Whether or not airfare is counted as an export or import depends on whether one uses a U.S. based airline to travel out of the U.S. or a non-U.S.-based airline to fly. See here for more detail.

Technically, I am discussing here the nominal exchange rate, which is simply the ratio of the two currencies. When studying international macroeconomics, you also want to consider the real exchange rate, which is the nominal exchange rate multiplied by the ratio of the relative price indexes of each country. The real exchange rate incorporates the fact that across the borders the price of goods and services will differ. Hence, when understanding how much it will cost to travel, you need information on the nominal exchange rate and the relative price differences of the goods and services in each country.

It is not uncommon for exchange rates to be quoted with the ratio written as I have written it, or with the ratio flipped (and the Canadian dollar on the bottom).

Another way of “seeing this,” is that if the exchange rate is 1.44, that implies the holder of a Canadian dollar would only get 69 cents worth of U.S. currency (if they exchanged their Canadian currency for U.S. currency). If the exchange rate fell to 1.04 as in my example, the holder of a Canadian dollar would then get 96 cents worth of U.S. currency—hence, the Canadian dollar would be worth more relative to the U.S. dollar than it was before.