On Wednesday of this week the Fed will announce an increase in their interest rate “target.”

Evidence for a booming economy keeps rolling in—in spite of much apprehension and worry over Russia, gas prices, and the refusing-to-die-down rate of inflation. The latter of course, is a key piece of that evidence. The other is the historically low unemployment rate, which came in at 3.8 percent for February. But, I have already emphasized these data in previous posts.

The point of this post is to answer the question of “why the interest rate?” Why doesn’t the press talk more about, say, our money? Doesn’t the Fed control our money? Isn’t that what matters? Why, then, do we always hear about the Fed’s interest rate “target?” The answer is straightforward, but with a subtle and important twist. Let’s start with the straightforward.

The Interest Rate is a Cost

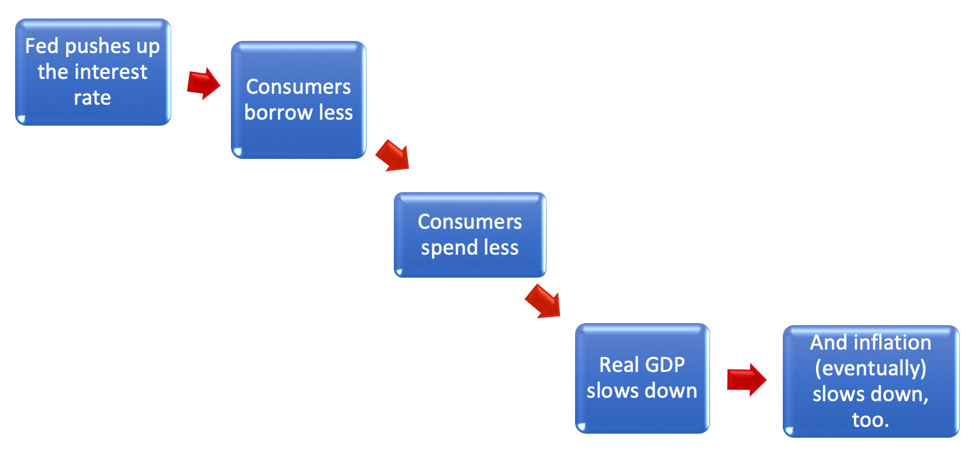

As consumers, we all have a direct understanding of why the interest rate matters. It’s part of the cost of borrowing. As rates go up, it becomes more expensive to take out a car loan or a mortgage loan. For many, that implies we borrow less or not at all. The Fed exploits that simple implication to carry out stabilization policy. Think of it this way:

This sequence of events is an important part the Fed’s attempt to stabilize the business cycle. But, what if many of us already have a mortgage? Or are not in the market for a car? Or, have enough cash on hand to get car without a loan? Can the Fed still clamp down on inflation via the above sequence? Yes, because there is more to the interest rate than its role as the “cost of borrowing.”

The Interest Rate is an Opportunity

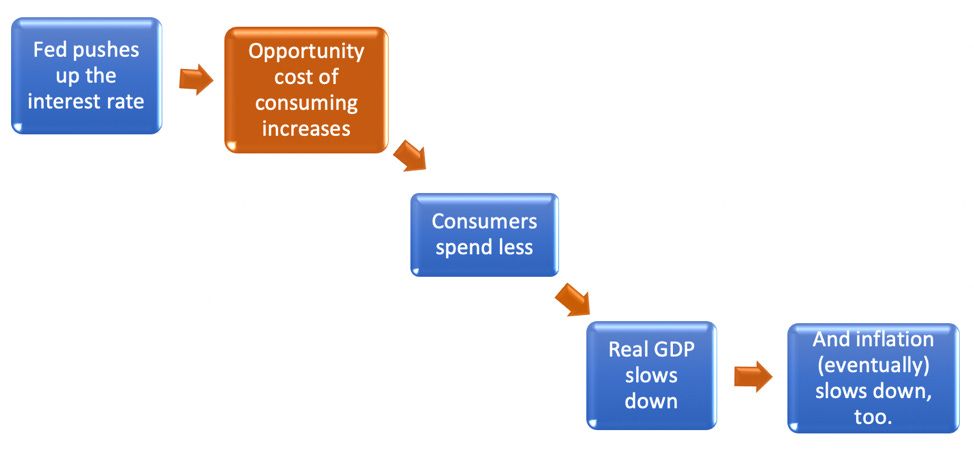

The interest rate is an opportunity, an opportunity to earn more money. If you spend your money on things today, you are giving up the opportunity to earn interest on that money. The latter implies you could have more money to spend tomorrow. For this reason, economists think of the interest rate as the “opportunity cost” of consuming. And, by extension, by consuming today you are giving up the opportunity to consume more tomorrow (all else equal).

Regardless of whether or not you need or want a loan, the change in the interest rate has an effect on you. If the interest rate increases and you still decide to spend your money on stuff, you are “paying” a higher price for buying that stuff. Again, you are giving up an opportunity, the opportunity to earn interest on that money.

In that respect, the mechanism really works like this:

Not everyone, of course, will react or even notice a change in the interest rate. The Fed just needs enough people to react—to change their behavior and cut back on consumption.

The “interest rate as opportunity cost” is the more complete way to understand the effect of Fed policy on consumer behavior. And while I’ve focused on consumers here, this mechanism also matters for companies. A change in the interest rate alters if a project or some expenditure by a company is going to be worth it or not, relative to what that company could earn on its cash, just like you could.

Which Interest Rate?

The explanation above is akin to what you would read in an “introduction to macroeconomics” textbook. The explanation keeps it simple by referring to “the” interest rate. Yet, in reality there are many interest rates out there. And, the Fed directly controls only a few of them. One of those rates is the “Federal Funds Rate”(FFR). The FFR is the rate the Fed has in mind when it refers to its “target” interest rate.

From our perspective—regular people going about our daily lives—the FFR is not very relevant. It’s not as if Toyota or Ford Financial are going to quote you the FFR when offering you a car loan. Rather, the FFR is the interest rate that banks charge each other to lend and borrow money between each other. Yes, that’s something that banks actually do, and they do it a lot. This borrowing and lending between banks occurs daily, meaning the terms of the loan last one day. For this reason, the FFR is referred to as an “overnight” rate.

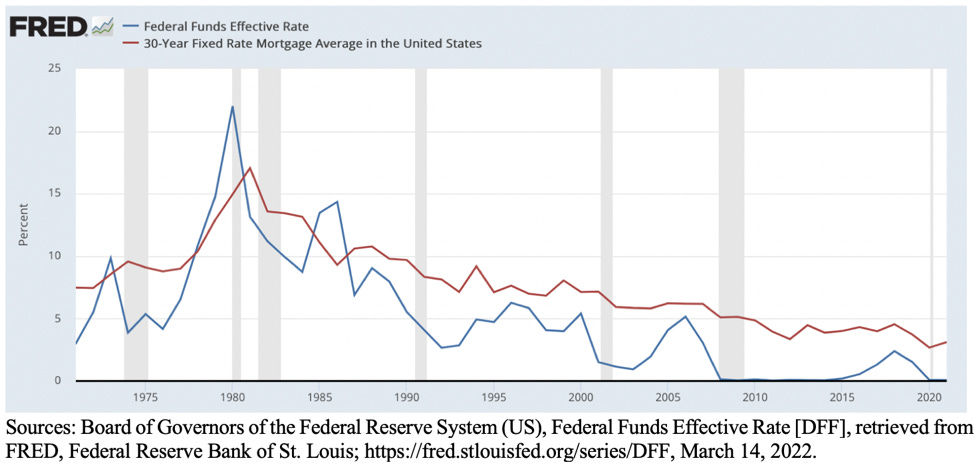

The FFR is the shortest of the short, in terms of interest rates. In contrast, you can compare that to the longest of the long—the 30-year mortgage interest rate. That is a rate, of course, that we are more familiar with. What does the FFR have to do with the 30-year mortgage rate?

The gist is those two rates, the shortest of the short, and the longest of the long, are connected, as if by a string. When the Fed manipulates the FFR up or down, the mortgage rate will follow suit, in time, and to a varying degree. The connection isn’t exact. The string is not tight and inflexible; rather, the string is loose and even a bit elastic. But, the connection is there. The figure below shows the two interest rates over time, since 1971.

Over this period, the correlation coefficient between these two interest rates equals 0.87 (if the variables are measured at the annual frequency, as shown in the figure). If the series are measured at the monthly frequency, the correlation equals 0.91. Recall, the correlation coefficient between two variables measures how connected their movements are over time. The highest positive correlation is 1.00, which implies that if one variable increases by 3 percent (for example), the other variable will increase by 3 percent. If the correlation coefficient equals 0.00, there is no connection.

The importance of the relationship between the FFR and the 30-year mortgage rate is thus: The Fed seeks to affect our spending behavior via the connection between the FFR—which they manipulate directly—and other interest rates in the economy, such as the 30-year mortgage rate, which affect us directly.

As the Fed changes its “target” value for the FFR, they do so assuming that such a change will eventually get to us. That idea is at the heart of how the Fed carries out their mandate to manage the business cycle.

In closing, please note that I have simplified the ins-and-outs of the Fed’s focus on interest rates. There are many aspects and details to all of this. Such as, how does the Fed manipulate the FFR in the first place? Or, does this always work? Or, how much does this really matter? For example, on Wednesday, the Fed is likely to announce they are raising their “target” value for the FFR by “25 basis points.” That’s fancy finance talk for 0.25 percent.

If the FFR is essentially zero, like it has been for the better part of the last 12 years, then what difference does a small change like 0.25 percent in the FFR really make? We’ll take up these questions, and more, in future posts.

Thanks Ryan! Appreciate your work and thoughts - very helpful.