Boring news is good news for the macroeconomy. The Bureau of Labor Statistic’s (BLS) CPI rate of inflation reading for September came in at the same value as the previous two months—0.2 percent (or, about 2.4 percent annualized). That month-to-month stability is good for the macroeconomy, but boring for macroeconomic discussions.

The good news for me as a macroeconomics instructor, however, is that my students seem pretty bored with anything I say—no matter how exciting or unexciting the data—so, the BLS’s report didn’t affect things in my class either way.

For example, this week we covered the topic of money. “Oh, that’s exciting!” you might be thinking. I’m sure my students thought that, too, at the beginning. But rather than learning the secrets of making money (I don’t know any), we covered how we, in the U.S. macroeconomy, define what is or what is not money. So, in the spirit of exciting-but-boring macroeconomics, let’s talk about money!

Money: it may be what you thought it was

What we consider “money” in our economy is specific. This includes what we commonly think of as money—cash and coins—as well as how we hold our money, in checking accounts and savings accounts, for example. The two primary labels for our money are “M1” and M2.” Historically, M1 and M2 were defined as shown in Table 1.

(See footnotes for explanations of “other checkable deposits,”1 “Money market deposit accounts,”2 and “Retail money market mutual funds,.”3)

The distinction between M1 and M2 is based on “liquidity,” meaning the ability to use something as money immediately for a transaction. Both currency and checking accounts allow for immediate transactions. The added categories to M2 also can be used for transactions; however, accessing the money in those types of accounts may come with a delay. For example, if you have funds in a three-month certificate of deposit, you have to wait three months to access that money (or pay an expensive fee to claim the money before the three months is up).

Notice however that many of the accounts listed in Table 1 are probably pretty close to being as liquid as checking accounts (or currency). If you needed to transfer cash from your savings account to your checking account—in order to use your debit card for some purchase—you could do so extremely quickly from the banking app on your phone.

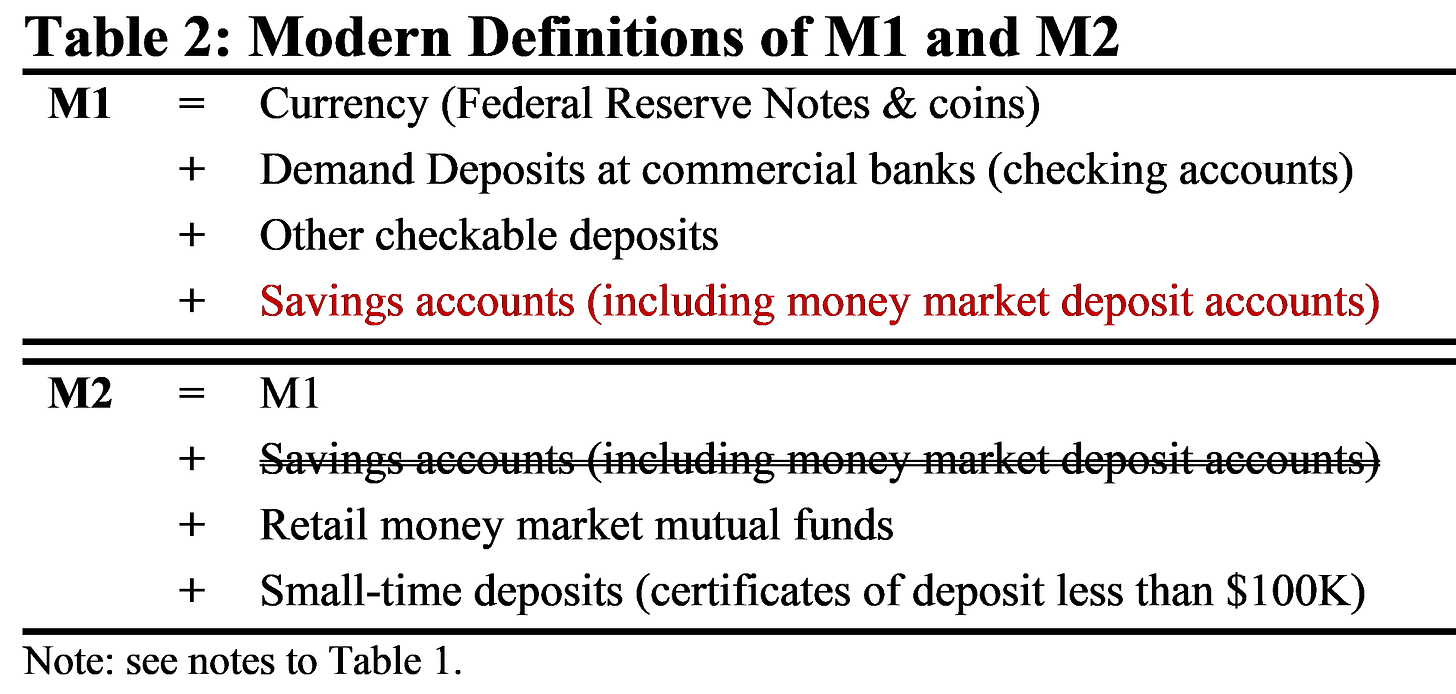

Recognizing that the liquidity of savings accounts has increased over time, in 2020, M1 was redefined to include savings accounts, including money market deposit accounts.4 Hence, since the middle of 2020, M1 and M2 are now defined as shown in Table 2.

Notice the only difference is moving the item “Savings accounts (including money market deposit accounts)” to M1. Since M2 includes M1, the total amount of M2 is unchanged.

Did this definitional change matter for the macroeconomy? No. The distinction between M1 and M2 is about liquidity, as mentioned. Meaning, what form of our money is available for immediate use. The change in definition did not change the total supply of money in our economy—which is represented by M2.

Our money over time

Figure 1 displays M1 and M2 at the monthly frequency (seasonally adjusted) since 1959.

Some comments:

One, you can see the change in the definition related to M1 and M2 discussed earlier. In 2020, all of sudden M1 shot up. Most of that was due to that change in definition.

But, that is not to say the total money supply did not increase drastically for other reasons. Indeed, M2 reveals that, while our money supply has always been going up, it especially increased from spring of 2020 to the spring of 2022 (the peak for M2 seen on the figure occurred in April of that year).

Why did our total money supply (M2) increase over that time period? First and foremost because of the massive stimulus spending that occurred in 2020 and 2021 (discussed in this Macrosight post). It is not a coincidence we see M2 increase over that period.

After early-2022, M2 declined. But since late-2023, M2 has been climbing again.

How does the increase in Money matter?

What did the spike in M2 starting in 2020 mean for the macroeconomy? A lot. Just as it is not a coincidence that we saw the spike in M2 coincident with the stimulus spending of that era, nor is it a coincidence that we experienced rapid inflation soon thereafter.

Next week I plan on boring my students with the thoughts and theories of macroeconomists on the connection between the growth of our money supply and the rate of increase in the prices of of our goods and services (a.k.a, the rate of inflation). Assuming we do not experience some exciting macroeconomic event between now and next Friday, I’ll plan on boring you, Macrosight reader, with that, too.

“Other checkable deposits” (OCDs) includes checking accounts other than the typical checking account at commercial banks. These include Negotiable Order of Withdrawal (NOW) accounts, which are similar to regular checking accounts but may require a minimum balance to earn interest; Automatic Transfer Service (ATS) accounts, which automatically transfer funds from savings to checking to cover checks or meet minimum balance requirements; Credit Union Share Draft Accounts, which are similar to checking accounts at banks but are offered by credit unions; and any other type of account at other financial institutions that allow at least some check-writing ability.

Money market deposit accounts are deposit accounts are similar to savings accounts but typically offer higher interest rates, with some check-writing and withdrawal privileges. These accounts are FDIC-insured.

Retail money market mutual funds are not deposit accounts but instead are mutual funds offered by investment companies (not banks) that invest in short-term, low-risk securities like Treasury bills (short-term government bonds), commercial paper (bonds issued by corporations), and certificates of deposit (CDs). These accounts are not FDIC-insured.

This change was motivated, in particular, by a change to regulations that occurred during the Federal Reserve’s policy responses during the Covid-19 pandemic. Those regulations removed outdated restrictions on savings accounts, rendering those accounts as liquid as checking accounts.