No one needs reminding it’s an election year, yet here I am doing just that. Why? Because this is a good time to explain how “government spending” matters for measuring GDP, and what it means for presidential candidates. On the latter, it is natural to wonder if presidential administrations seek to stoke the economy in advance of an election. This idea is the thrust of the theory of the “political business cycle.” On the former, maybe it is not so natural to wonder about how it matters for GDP measurement, but it is certainly important.

To address both issues, let’s first understand what government expenditure is, and is not.

Government Expenditure, not Government Obligations

Last week, Macrosight broke down the “I” in the iconic GDP-accounting identity, “C + I + G + NX”. Now it is G’s turn. Like “investment expenditure,” “government expenditure” is probably not exactly what you think it is.

The “G” in C + I + G + NX accounts for everything that our local governments, state governments, and our federal government spend on things that are analogous to consumption expenditure and investment expenditure. This includes the services government provides, such as National Parks and National Defense, as well as the equipment, structures and infrastructure required to produce public services.1

What government expenditure does not include, however, is what we often think of when it comes to “government spending”—social security payments, Medicare, and so on. Those types of government obligations are called “transfer payments” since they represent an allocation of money. From a budgetary-point of view they represent an expense of a sort, but, such a transfer of funds does not directly represent a newly produced good or service. Since GDP is meant to measure the latter, the category “government expenditure” excludes transfer payments.2

The G Shares

Figure 1 displays the share of government expenditure to GDP along with the shares of consumption and investment expenditure previously discussed in this space.

From 1950 through 2023, the average share of government expenditure has been 21percent. Over time the share has come down a little. Since 1990, for example, the share has been about 19 percent, while prior to 1990 the average was closer to 22 percent. In 2023, the share was 17 percent, which equated to about $3.8 trillion (2017 constant dollars).

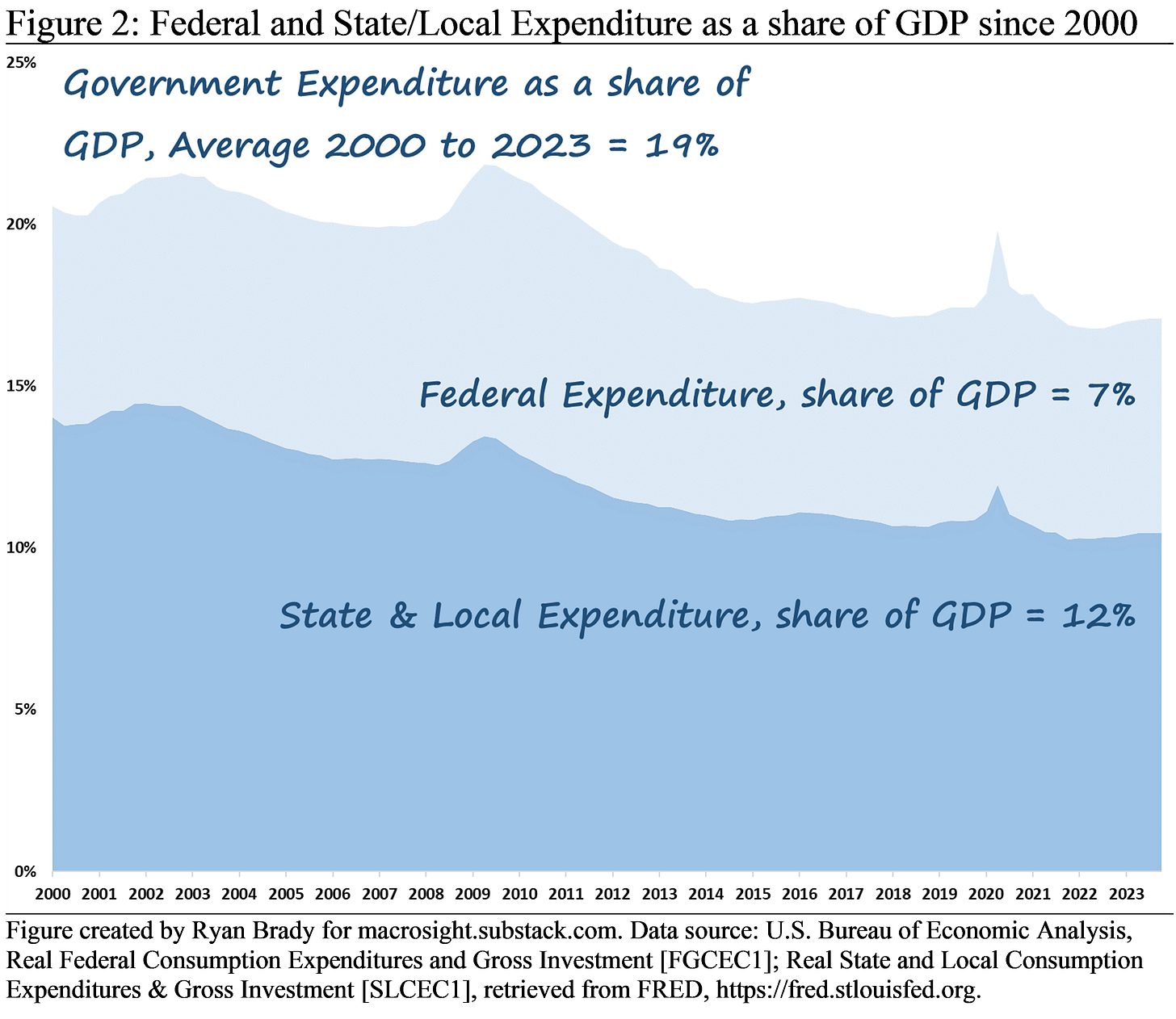

As noted above, government expenditure is comprised of federal, state and local spending. Figure 2 displays the shares of these sub-categories relative to GDP since 2000, at the quarterly frequency (note that state and local are combined into one in the NIPA accounts).

Federal expenditure makes up the smaller share of total government expenditure (which may come as a surprise to some), averaging about 37 percent of the total since 2000 (in 2023 the share was little higher at 39 percent). Relative to GDP overall, the federal share has averaged about 7 percent since 2000. In 2023, the share was also 7 percent. This amounted to about $1.4 billion in federal expenditure in 2023.

The remaining 63 percent of government expenditure is comprised of expenditure at the state and local level. The share of this sub-category to GDP has averaged about 12 percent since 2000 (and was about 10 percent in 2023).

Smaller share or not, if a presidential administration wished to goose the economy by increasing government expenditure, it stands to reason it would have more influence over federal spending versus state and local. With that backdrop, what can we say about federal government expenditure in election years?

Nothing to See Here?

Figure 3 displays the annualized quarterly growth of federal government expenditure since late-1999. The figure is color-coded blue (Democrat) and red (Republican) to identify the last few quarters of Clinton’s second term, and the Bush, Obama, Trump, and Biden terms, respectively. The bars emphasized in black identify the fourth quarter of a presidential election year. The bars shown in either red or blue identify the four quarters proceeding the quarter in which the election occurred (for example, for the 2000 election year, those four quarters are 1999Q4 through 2000Q3).

What can one take away from this figure? With respect to the fluctuations in federal expenditure quarter-to-quarter, the sub-category looks somewhat volatile. The average growth rate from 1999Q4 to 2023Q4 is 2.1 percent and the standard deviation is 6.2 percent. If we restrict the sample to 2000 through 2019, the average growth rate is 2.2 and the standard deviation is 4.7—which is higher than consumption expenditure but lower than investment expenditure over the same period (the standard deviation of total government expenditure from 2000 to 2019 period is 2.8 percent).

With respect to election years, is there any visual insight we can draw? Probably not much. There does not appear to be a consistent pattern of an increase in federal expenditure in the four quarters leading up to the quarter in which the election occurred. But, let’s take a closer look at each election.

2000: In the run-up to the 2000 election, federal expenditure was up and down. Like Al Gore’s Lock Box, there does not appear to be much going on here

2004 & 2008: During the Bush administration the growth rate of federal spending was positive in each of the four quarters prior to both the 2004 and 2008 elections. Perhaps this suggests some business-cycle goosing? Yet, in both cases we were at war and in the case of 2008, the economy was deteriorating. In February of 2008, the U.S. Congress passed the Economic Stimulus Act in response to the latter. It’s possible many in Congress and the White House could have supported such an act in hopes the economy would be strong come November for the Republican nominee. But, that Act was passed in the House with 380 “yeas” to 34 “nays,” and 91 in favor and only six against in the Senate.

2012 & 2016: In the eight quarters proceeding the 2012 and 2016 elections, federal expenditure showed negative growth or nearly zero growth in five of them. The three quarters with positive growth were some of the lowest rates in the 24 year period shown on the figure. So, there is not much to support the idea of a “political business cycle” leading up to these elections (various factors explain the anemic growth of federal spending during this era, see this article for discussion).

2020: In the first half of 2020, federal spending obviously sky-rocketed from the various executive and Congressional acts that occurred during that time. It seems reasonable to infer that the increase in spending as provided by measures such as the CARES Act (passed March 27th) was Covid-19 related. And like the 2008 Stimulus Act, the CARES Act was passed with bi-partisan support—419 to 6 in the House and 96 to 0 in the Senate.

2024: Given my timeline of “four quarters before the election,” it is too soon to assess matters for the up-coming election. Given the economy appears to be on solid footing for now—an assessment reiterated with this week’s release of the BEA’s second estimate for 2023Q4 GDP—I would not bet on any stimulus bills in the near future (though things can change quickly, of course).3

No Smoking Gun

One additional check we can do is look at the “typical” federal spending patterns for each administration over the four quarters prior to the election (emphasized with the red and blue bars in Figure 3), compared to what occurred the rest of their terms. Table 1 displays the average growth of federal spending prior to each election, demarcating between the previous four quarters and the 11 quarters prior back to the beginning of each four-year term.

Like the inference based on Figure 3, there does not appear to be a smoking gun here with respect to the “political business cycle.” Only in 2008 and 2020 was the average growth of federal spending higher than the proceeding 11 quarters of those administrations’ terms. But, we already explained those particular cases above.

While the analysis in this post does not prove or disprove anything, the data doesn’t support the notion that presidential administrations try to juice the economy with extra federal expenditure prior to the next election—at least not in the last quarter-century. The inference in this post, too, supports a recent claim that while the political business cycle may have been a thing in the past, it no longer seems to be so today.4

See Chapter 9 of the NIPA Handbook for more detail on both government consumption and investment expenditure, at https://www.bea.gov/resources/methodologies/nipa-handbook/pdf/chapter-09.pdf.

Summed together, transfer payments and government expenditure make-up what are referred to as government “outlays.” In practice, government expenditure makes up the bulk of outlays. The difference between total outlays and expenditure was about $200 billion in each of the past three years. Also, the computation of the difference is more detailed than presented in this post. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provides a concise explanation here (see Table 3, in particular).

Consumer spending for January 2024 showed a 0.1 percent decline (after increasing 0.6 percent in December 2023). While a monthly decline in consumer spending does not necessarily imply macroeconomic peril, if consumer spending falls again in February then one might start to worry about the macroeconomy.