Fed independence means we avoid the “Werewolf Problem,” as Macrosight explained here. Yet, what restrains the non-elected officials running the Fed from turning into werewolves themselves? The answer: Credibility.

Say what you do and do what you say

Credibility in the context of central banking means the same thing it means in regular non-central banking life. You are credible if you do what you say, and say what you do. The Fed states publicly that they seek a stable rate of inflation of 2 percent. The Fed is perceived as credible if its actions adhere to that stated goal and the outcomes of its actions conform to that goal.1

Credibility matters a lot in central banking, since it is a well-accepted tenet of the subject that a credible central bank is an inflation-controlling central bank. If everyone believes that the Fed will take action to fight inflation—should inflation flare up unexpectedly—and the Fed does in fact do so, then inflation will remain low and stable. If the Fed instead turns into a werewolf, falls down on the job, and inflation runs amok, their credibility is shattered and inflation will only get worse.

So, is the Fed credible?

Beastflation and Credibility

Is the Fed credible? Now, here in 2024? Yes, I think so.

But, they came pretty darn close to losing their credibility over the Beastflation debacle from 2021 to 2023. As this blog has stated before, the Fed dropped the ball on inflation starting in 2021. Jerome Powell and his Fed colleagues mis-read the inflation picture, thinking (like many at the time) that inflation in 2021 was “transitory,” the result of “supply-chain problems.” They didn’t quite grasp in real-time in 2021 that, amidst record-setting amounts of stimulus money engorging the wallets of the Hungry Beast, consumer spending and real GDP were soaring to record levels.

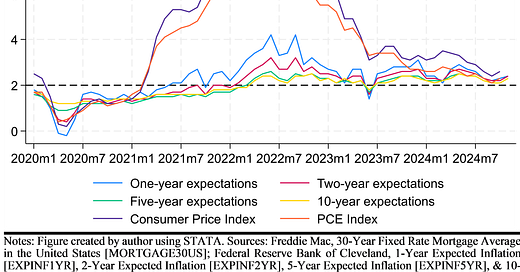

How do we know that the Fed nearly destroyed their own credibility as inflation-fighters? Because markets told us so. Figure 1 displays monthly measures of inflation expectations at the one-year, two-year, five-year and ten-year horizons—that is, what market participants think inflation will be one year from now, two years, and so on. These expectations are assessed every month; the figure displays the statistics starting in January of 2020.2

Notice first the blue and red lines—the measures for expected inflation one year and two years from now. Starting in mid-to-late 2021, both of these series started to jump up. By mid-2022, markets were expecting inflation of around 4 percent one-year from then. For the two-year picture, expectations were a bit less, with inflation of about 3 percent expected two-years on.

The increases in those series suggest the following: markets didn’t expect the Fed to reign-in inflation back to 2 percent anytime soon. Everyone knew the Fed’s target was 2 percent. Yet, by mid-2022, markets still expected inflation of around 4 percent out to mid-2023.

Do those expectations series mean the Fed lost its credibility? To some extent, yes—at least in my opinion. The expectations data suggest markets understood that the Fed had lost the handle on inflation in the near-term and it would take the Fed a while to get it back under control.

On the other hand, the expectations data also reveal that market participants did not completely lose faith in the Fed as credible inflation-fighters. Notice the green and yellow lines. Those series reveal what markets believed inflation would equal five and ten years out, respectively. While each of those series did tick upwards, they each remained relatively muted—about 2.5 percent or less—throughout the Beastflation period.

Considering that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) reached 9 percent in June of 2023, the fact that inflation expectations at those longer horizons remained below three percent is notable. If the Fed had really lost its credibility with markets, we would have seen much higher levels for the expectations series.

Figure 2, for example, plots the CPI (the purple line) and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI) (the orange line) along with the inflation expectations data.

Inflation as measured by both the CPI and the PCEPI went above 2 percent in early 2021; yet, the one-year expectations series did not go above 2 percent until a few months later. The two-year, five-year and ten-year expectations did not go above 2 percent until much later. That suggests one of two things (or both): market participants also thought that inflation was transitory and/or that eventually the Fed would do its thing.

Notice also that the actual increase in inflation (measured by either the CPI or PCEPI) is much more dramatic than any of the expectation series. With that in full view, the relatively tepid rise of inflation expectations underscores the point I made just above: the expectations data suggest that, for the most part, the markets believed the Fed would get inflation under control at some point.

Indeed, once the CPI and the PCEPI began to disinflate in the summer of 2023, the expectations series almost immediately began to decline as well. This is why in response to the question posed earlier, “Is the Fed credible? Now, here in 2024?”, I responded in the affirmative.

A Return to Glory?

Does this argument suggest that the Fed’s reputation as a swash-buckling, Just Do It, inflation-fighter is fully restored?

Maybe not quite.

Table 1 shows the values of the CPI, PCEPI, and the expectation series for this October and November; as well as the Fed’s forecasted values for the rate of inflation for 2024 and for the “long run”(published coincident with their September meeting).

Notice the following:

Both the CPI and PCEPI rates of inflation are up relative to October. While this is not necessarily something to be alarmed about (inflation as measured by both series have remained below 3 percent since July), it would certainly have been preferable to see inflation tack downwards in November.

Coincident with the increase in actual inflation, expectations of inflation at all future horizons have also increased.

The expectation series reveal, too, that markets do not buy the Fed’s projection for 2024; inflation expectations for one and two years from now are slightly above the Fed’s 2.3 percent forecast for the end of this year (the expectation of 2.4 percent is not that far off, of course).

Finally, notice also that current long-run expectations (the five and ten-year series) are above what the Fed has projected for inflation in the long run—its target of 2 percent. For the Fed, the “long run” is anything beyond three years (as can be seen in their projection table here). Hence, market participants do not appear to believe the Fed is going to hit its 2 percent target even four years from now.

So, what to make of all of this evidence? I would say on balance it appears the Fed’s credibility remains intact. Markets never gave up on the Fed entirely, even amidst the blight-on-its-reputation that was Beastflation. That is how I read the expectations data. But, as the expectations data also suggest, the Fed still has some work to do to re-burnish its hard-earned reputation of yesteryear.

In the opening paragraph to this post I could have written the answer to my own question as “The Answer: Credibility and Accountability.” In the interest of keeping the post relatively concise, I chose to emphasize the former. Accountability means the Fed has to answer for its actions and outcomes. The Fed is held accountable in a number of ways. One, they communicate regularly with the public (Jerome Powell holds a press conference after every meeting); they publish their forecasts; they publish the minutes of their meeting a few weeks after said meeting; they publish transcripts of their meetings (though with a five-year delay); Jerome Powell meets with Congress twice a year; and, finally—and perhaps most importantly—financial markets hold them accountable. The last one is discussed in this post.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland publishes an “Expected Inflation” forecast for various time frames—for the next year, two-years, five years and ten years. The Cleveland Fed generates their measures of inflation expectations from a combination of financial data, inflation data and surveys. The current forecasts and additional documentation are found here on the Cleveland Fed’s website. Macrosight has discussed this data previously in this post and this post.