To the annoyance and bafflement of nearly everyone involved in the housing market, the 30-year mortgage rate has increased by almost 50 basis points (or half of a percent) over the last month. This is in spite of the fact that a little over a month ago the Fed went big with a 50-basis point cut of the federal funds rate.

The conventional wisdom is that if the Fed cuts the federal funds rate, then all other rates will follow (as explained here by Macrosight). That should especially be case for interest rates on very long-term financial contracts, like, say, a 30-year mortgage.

And, that should especially, especially be the case here in the fall of 2024. Long-term interest rates like the 30-year mortgage rate include an “inflation premium.” That means if lenders think inflation is going to increase, they increase the offered 30-year rate by some amount. If inflation is low and stable, and lenders expect inflation to continue to be low and stable, that inflation premium should be smaller than otherwise. Hence, if the inflation premium is lower, the 30-year mortgage rate should be lower, all else equal.

Given that logic, the increase in the 30-year mortgage rate the past month is not what anyone would have expected following the Fed’s rate cut. The Fed even stated that they had “gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent,” in the press release announcing the cut.

So, what the heck is going on?

My first thought, as a macroeconomist, is to look at inflation expectations.

It’s the Expectation

Inflation expectations are one of the key drivers of inflation itself. If we, consumers, firms, bankers, and just about anyone affected by inflation, think that inflation is going to rise, that expectation turns out to be an important determinant of what actually happens with inflation (Macrosight explains this in more detail here).

So, if the 30-year mortgage rate has increased the past month, does that mean inflation expectations have also jumped? Well, let’s see.

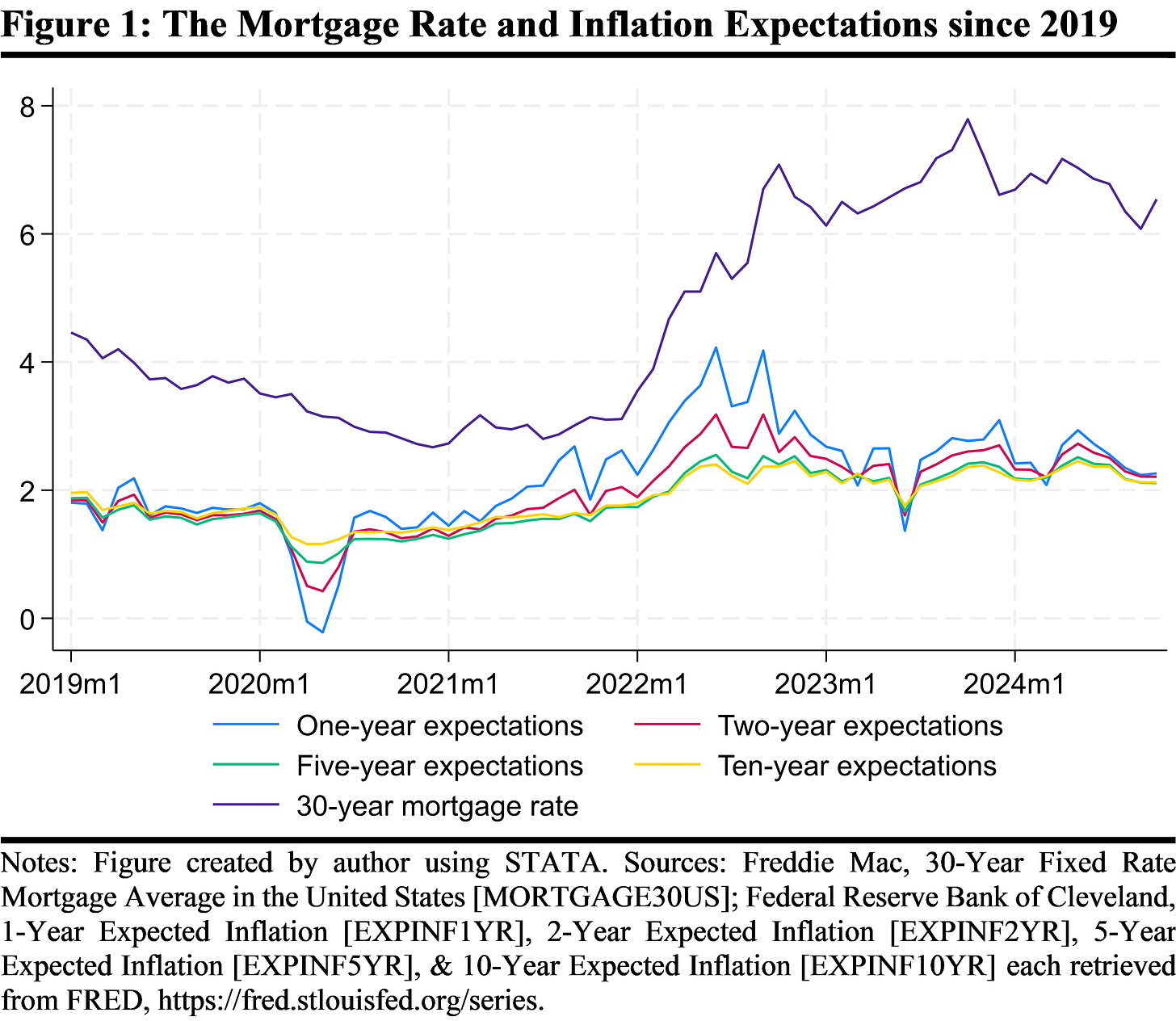

Figure 1 displays the 30-year mortgage rate, and inflations expectations at the one, two, five and ten-year horizons.1 The timeline displayed is from January 2019 through October 2024.

Some things to notice in Figure 1:

The mortgage rate started spiking in late 2021, peaked in the latter part of 2023, and was relatively volatile in between. We can see, too, at the very end of the series the 50 basis point increase mentioned at the outset of this post.

Inflation expectations at the four different time-horizons track each other pretty closely. Yet, expectations at the shorter horizons (one and two year) are more volatile that the five and ten-year. That is because there is more uncertainty in the near-future about what to expect for inflation.2

Over the last few months, inflation expectations at each horizon have trended downwards.

We can see the last point more easily in Table 1, which shows the values for those series for each of the past six months.

As revealed in Table 1, inflation expectations have declined over the past six months, and the past couple of months they appear quite stable. The latter is important because it reveals that the uptick in the mortgage rate this past month is not due to an increase in inflation expectations. While the one-year expectation ticked up from 2.24 to 2.26, it seems implausible such a small increase would drive an increase in the mortgage rate of 50 basis points.

I think it is safe to infer that the spike in the 30-year mortgage rate is not associated with expectations of higher inflation. So what could it be?

Supply & Demand

The easy answer to any question in economics is “well, it’s because of supply and demand.” But in this case, I suspect that is the answer—in particular the latter. Specifically, it appears that coincident with the drop in the Federal Funds rate the past month, metrics tracking the demand for mortgages reveal an increase.

For example, the website “Mortgage News Daily,” shows that an index of mortgage applications for home purchases has been on an upward trend since late-July-to-early August. This is true, too, for a separate index focusing on refinancing applications.3

These data suggest the demand for mortgages has been increasing, even before the Fed cut the rate by 50 basis points. The momentum from that increase helps explain why mortgage rates have increased. In this case, the demand signal has been strong enough to push up the rate in spite of the Fed’s policy change.

Note, too, that the demand for mortgages is tied to the demand for housing. Average home prices have leveled off the past few months (as measured by the Case-Shiller index or by the FHFA index4). Falling average home prices are likely to be correlated with an increase in the demand for housing and for the mortgages needed to buy them.

The forces that determine the 30-year mortgage rate are many—tied to the demand and supply of mortgages and the demand and supply of housing, inflation expectations, in addition to other possible factors associated with financial markets more broadly. In the curious case of the 50 point bump over the last month, I think it is safe to rule out inflation expectations. Based on this limited look at some mortgage data, it seems that demand may be the culprit.

That is, these series reveal what market participants believe inflation will be in one, two, five and ten years from now—Macrosight discussed the details of this data source in the post linked to earlier in this post.

Ironically, even though the farther-off future is more uncertain in general, inflation expectations for those horizons appear more certain. That is because expectations at longer horizons tend to conform to a “best-guess,” which is some long-run average of what inflation has been. So, in this case, our best guess of the long run inflation rate is going to be about 2 percent—that is about what inflation averaged from 2000 to 2019, and that is what the Fed targets for the inflation rate.

If you click on these links, you can convert the graph on FRED to percent changes using the “Edit Graph” button. Then, it is easier to see the decline in these housing price indexes the past few months.

Thanks for sharing this great analysis, Professor Brady. Do you think the credit condition of consumers comes into play for this part? The earnings from banks in recent quarters seem to continue to show high credit card delinquency rate.