The Enduring Myth of Consumer Sentiment

Does it really predict consumer spending?

Like any good myth the following just won’t die: “Consumer Sentiment matters for consumption spending” . . . or something along those lines. Consumer sentiment gets a lot of attention in the media—as these various headlines attest—as if it provides a crystal ball into what is coming next for consumer spending. It makes sense that we might assume a survey of consumers—and how they feel about the economy—would help predict where consumer spending is headed.

For example, just today the Bureau of Economic Analysis released its estimate for consumer spending for April 2024. Consumer spending declined 0.1 percent over the course of April. One wonders, did consumer sentiment the past few months predict such a drop? Or, more generally, does consumer sentiment predict future changes in consumer spending?

Narrator: It doesn’t.

To do a bit of myth-busting, let’s look at some data.

An Oracle?

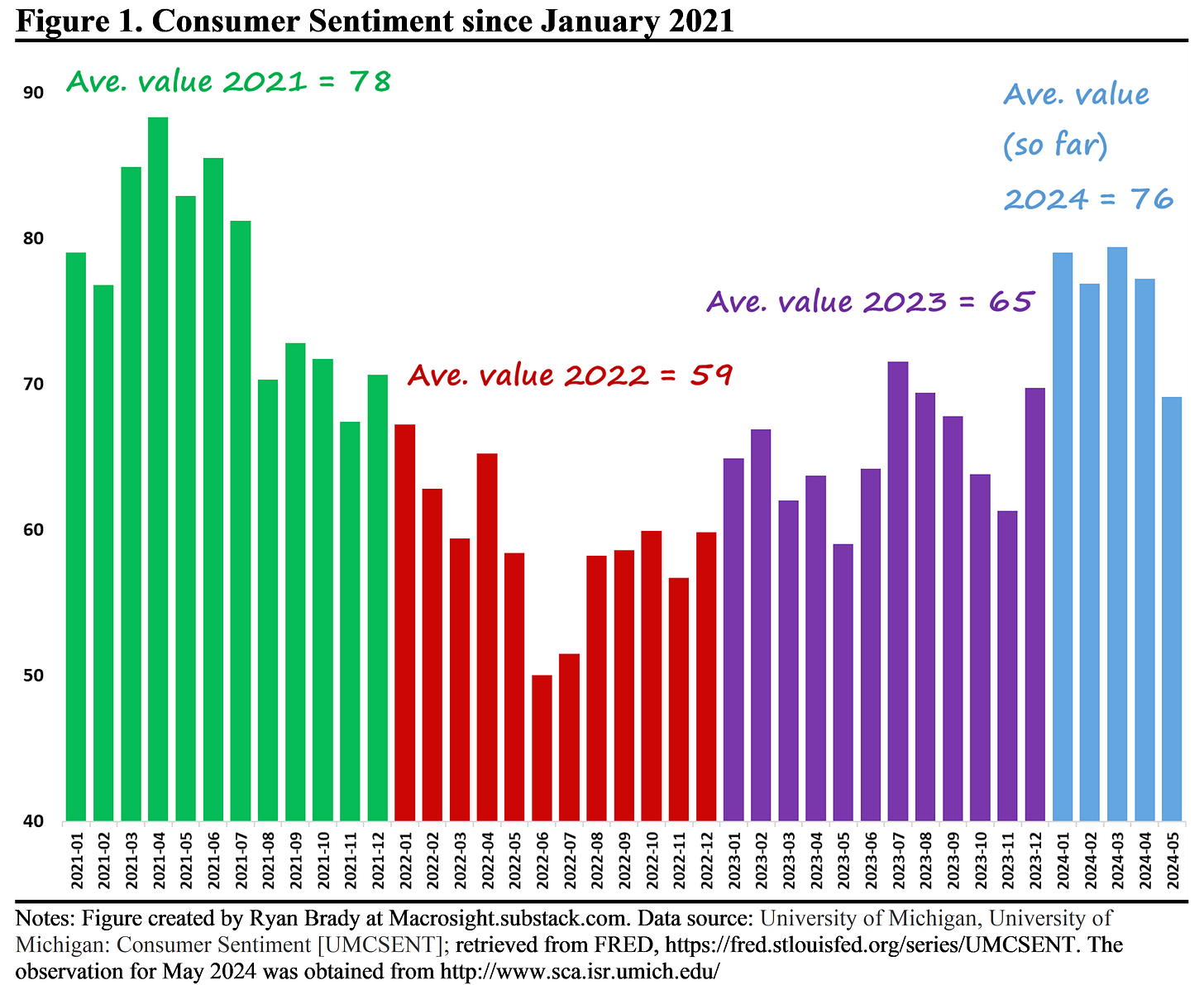

Figure 1 displays one popular measure of consumer sentiment, produced by the University of Michigan.1

The figure highlights the differences across the past three-plus years. During the heady-days of 2021, the index reached a peak of just under 90, and averaged just under 80 over the year. By the middle of 2022 the index reached a historic low of 50 (since 1978, when the series was first published monthly—see here for a longer time series). Now, four months into 2024, the average value is back to about where it was in 2021 (at least on average). Of course, one notices the latest value for April is the lowest reading this year—69 versus 77 in March.

What does this have to do with consumer spending? Not much, to be honest. At least not with respect to predicting consumer spending.

A Follower, not a Leader

Figure 2 displays the annualized monthly growth rates of consumer spending since 2021 (adjusted for inflation). The annotations on the figure show the average monthly growth rates for each year.

The pattern of average growth rates over the three-plus years, for the most part, syncs-up with the pattern we see in Figure 1. The high rate of consumer spending in 2021 matches up with the highest observed sentiment readings. The low sentiment readings of 2022 coincide with the relatively anemic consumer spending in 2022. It certainly appears there is some relationship, no?

Yes, but it is ultimately a coincident relationship, and a weak one at that.

Table 1 displays the correlation between consumer sentiment and consumption expenditure over different time periods in addition to the 2021 to 2024 time span shown in Figures 1 and 2. The correlation numbers allow us to see how these two variables “move together” over time.2

The correlation statistics suggest that the series are mildly correlated coincidentally. Values below 0.20 suggest weak correlation; values around 0.35 are not that strong either.3 For values of the sentiment index in previous months, the correlations are essentially zero. Looking across the time periods, for the most recent three-year period the correlations are higher, but that may be a reflection of the smaller sample size. Nevertheless, the magnitudes are not that large.

Of course, correlations are just that, correlations. They do not provide a crystal ball, just a relatively crude picture of how these variables move together through time (in this case, weakly).

A Forecast

If we estimate a more elaborate statistical model, we can say something a bit more concrete on the predictive relationship between the two variables. Figure 3 displays the results of what is called an “in-sample” forecast. The figure shows the forecast of consumer spending for eight months following a positive “shock” to consumer sentiment in month 1.

The figure reveals the following: about one month after the “shock” to consumer sentiment, consumer spending increases by a smidge. Thereafter the responses to the “shock” oscillate around zero. The dashed lines, too, reveal the following: the response of consumer spending to the change in consumer spending is not statistically significant.

In practical terms that means that consumer spending shows no response to the change in consumer sentiment.4 Or, consumer sentiment provides no predictive information about what consumer spending will do in the coming months. That doesn’t jive with the myth, of course. But that is what the data reveals.

The University of Michigan (UMICH) publishes the Index of Consumer Sentiment via their Survey of Consumers. Another popular measure is the “Consumer Confidence Index” published by the Confidence Board is not publicly available (meaning it is not free to download and analyze).

Macrosight previously discussed the relationship between consumer spending and sentiment in this post from 2022; in that post I explained (with some paraphrasing): “A correlation coefficient . . . provides a measure of how two variables “move” or change together over a sample. In our case, the sample is a period of time . . . the correlation of 0.20 . . . reveals a positive but not-so-strong correlation . . . A very strong positive correlation would be closer to 1 (a rule-of-thumb is that a correlation of around 0.70 and higher is “strong”).

The first row shows the “one month ahead” value of the sentiment index since the March observation of the index is reported the first week of March—so really it is capturing how consumers feel coming out of February. Whereas consumer spending data for each month represents an end-of-month value.

I should, add, too, the discussion provided in this post in generally consistent with the findings of a lot of academic studies. Consumer sentiment does not forecast consumer spending (only past values of consumer spending forecast consumer spending).