Tracking our Investments

Not that kind, the GDP-kind

When it comes to GDP and our macroeconomy, “Investment” expenditure is not what you think. Most of us hear the word “investment” and think of stocks and bonds, Wall Street or Warren Buffet. In GDP accounting, however, investment expenditure—officially dubbed “gross private domestic fixed investment”—refers to spending on stuff that is used to make other stuff. And while investments in stocks and bonds get all the attention, the investment component of GDP is there in the background, determining in part whether the business cycle goes up or down.

Spending on Things to make Things

Investment expenditure tracks the spending on the equipment, machines, buildings and other aspects of production that U.S. businesses do in order to provide us all the stuff we like to buy. The total amount of that spending, known as “business investment,” came out to about $3.3 trillion in 2023 (in 2017 constant dollars).

Investment expenditure also accounts for the money we as households spend on new homes or the renovations we do on our existing homes. This part of the category is dubbed, “residential investment.” The amount of spending related to residential investment in 2023 was about $734 billion (in 2017 constant dollars).1

Together those two parts of investment expenditure make up about 17 percent of total GDP, with business investment and residential investment separately comprising 13 and 4 percent of GDP, respectively.2

While those investment shares are clearly much smaller than the share of consumer spending, investment expenditure is special in its own way.3 Investment spending not only provides the tools of production to make the goods and services we consume today, but that spending also facilitates the provision of goods and services in future years. The investment expenditure flow of 2024, in other words, will add to the stock of our productive ability for many years to come. As such, any current-year rise or fall in either residential investment or business investment not only impacts current-year GDP directly, but future years of GDP as well (at least indirectly).

A GDP Prophet?

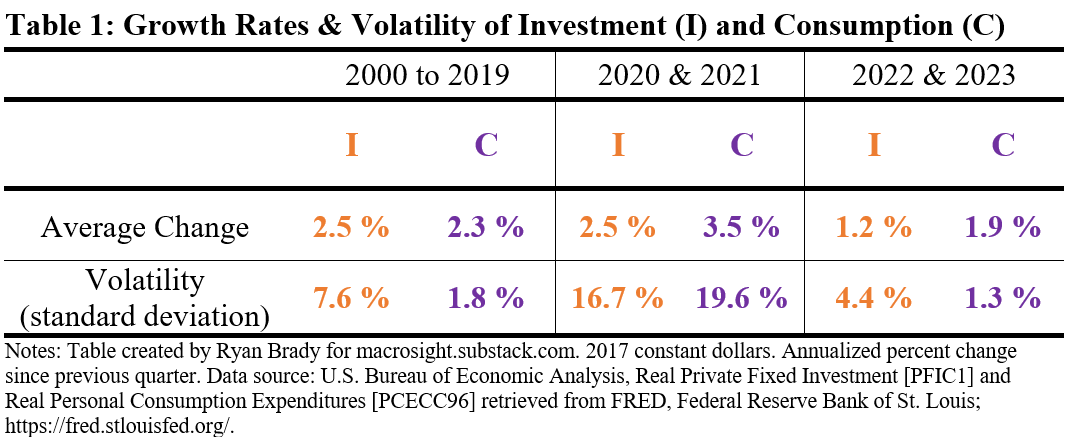

That description of investment begs the question: how does this category matter for our business cycle? Especially relative to consumer spending? Table 1 compares the average growth rate of investment expenditure (the sum of business and residential investment) to consumer spending, as well as the average volatility of these series. The table provides a comparison of the two decades prior to Covid1-19, to the two-year period spanning 2020 and 2021, and the two-year period of 2022 and 2023.

Looking across the columns of Table 1, one can see that the average quarterly growth rates for investment and consumer spending are generally similar in magnitude. Yet, the volatilities of the two expenditure categories are noticeably different. From 2000 to 2019, investment spending was much more volatile than consumer spending, by almost a factor of four. In 2020 and 2021, however, consumer spending was much wilder, though investment was still plenty wild itself. Over the past two years, things have returned to “normal”—if not gone below normal—as the numbers for 2022 and 2023 on average are closer to the values from 2000 to 2019.

The data in Table 1 suggest that when it comes to the business cycle, what investment expenditure lacks in relative share size compared to consumption expenditure, it makes up for in its volatility. To get a better sense of this, let’s look at the sub-categories of investment mentioned earlier.

Business and Housing

Figure 1 displays the fluctuations in both business investment expenditure and residential investment expenditure since 2000.

Given the data in Table 1 above, it is not surprising to see that the sub-categories of investment expenditure are quite volatile over time. This is especially true of residential investment expenditure (the blue line), where large drops are observed multiple times the past 24 years. This is notable in the quarters leading up to, and during the Great Recession, and since 2020.

Table 2 provides a similar comparison shown in Table 1, though with the focus on the average growth and volatility of business investment expenditure and residential investment expenditure.

Housing-related investment spending is clearly the most volatile. That is true as measured by the standard deviation, but that wildness is expressed, too, in the average growth rates from 2020 to 2021 versus 2022 to 2023. Investment spending on housing went from way above the historical average to way below that average. Perhaps one silver lining to that flip-flop, as we look ahead to the rest of 2024, is the decline in housing, as seen in Figure 1, came mainly in 2022. Over last two quarters of 2023, at least, the growth rates of residential investment were positive (at annualized rates of 6.5 and 1.0 percent, respectively).

An Omen of Doom?

The wild swings in residential investment are emblematic of the out-sized impact that the category of investment spending can have on GDP (again, in spite of its smaller relative share compared to consumer spending). For example, consider the effect this category has had on GDP growth the past few quarters. Figure 2 reveals how GDP growth was impacted by the change in residential investment over 2022 and 2023.4

Take the third quarter of 2022 as an example. In that quarter residential investment dropped 30 percent (on an annualized basis—this dip can be seen in Figure 1). What impact did such a large drop in this investment component have on GDP that quarter? Actual GDP grew at a rate of 2.7 percent that quarter. Yet, residential investment clearly served as drag on GDP growth, with that drag estimated to be about 1.4 percent (the negative1.41 percent shown on Figure 2). If residential investment had not changed at all that quarter, real GDP growth would have been 1.4 percent higher at about 4.1 percent instead of the actual 2.7 percent.

Perhaps, then, residential investment, or business investment expenditure, provide prophetic information on our business cycle. Does the abysmal performance of residential investment from 2022 portend our macroeconomic doom in 2024? Or will the relatively steady growth in business investment spending over the same time period—at 4.8% as shown in Table 2—serve as a buoy to GDP as the year proceeds? That is tough to say for sure, of course. What the data does tell us, however, is that it will probably be a wild ride, at least when it comes to these expenditure categories.

Residential investment speaks to a specific aspect of housing, new expenditure (recall that GDP focuses on the new). The BEA explains that residential investment, as accounted for in GDP, “includes capital expenditures for the acquisition of new residential structures and for improvements to existing residential structures by households in their capacity as owner-occupants”(NIPA Handbook, chapter 6).

There is a third category of investment expenditure known as “net change in inventories.” This category—which tracks the amount of inventories businesses accumulate or shed in a year—makes up less than one percent of GDP. In spite of its relatively small share of GDP, however, this category is unique when it comes to GDP accounting. As such it is deserving of its own Macrosight post, so we’ll save it for later.

Consumption spending comprises about two-thirds of GDP. Macrosight has discussed consumer spending a few times—its persistence, its relative smoothness over time, and its sub-components. Note also that in addition to consumption expenditure and investment expenditure, the other two main categories of GDP are “government expenditure” and “net exports.” Together these four make up the iconic GDP-accounting identity, “C + I + G + NX”. So far, Macrosight has yet to explore the “I + G + NX” parts of the identity. Well, finally it’s I’s turn.

This statistic is provided by the Bureau of Economic Analysis and published as “Contributions to Percent Change in Real Gross Domestic Product”(downloadable here). The “contributions” allow us to see how important each component (and sub-component) of GDP was to that quarter’s GDP growth rate (as explained by the BEA here). Macrosight previously discussed this statistic with respect to consumption.