Recently, a CEO of a major food brand mistook his foot for one of his products and suggested that U.S. consumers should deal with rising food prices by eating cereal for dinner. He seemed to be serious and thought he was offering helpful advice. Yet, much like the reaction to Marie Antoinette’s (alleged) famous quip, many were not as appreciative of the sentiment from the apparently-obtuse CEO.

Snap and Crackle, but no Pop

The CEO’s dining suggestion touched a nerve since while the Federal Reserve and other egg-heads out there are telling everyone that inflation is falling, it certainly doesn’t feel like it when we hit the grocery store. The reason for that is while disinflation1 is certainly occurring, disinflation still implies that prices are rising—just at a slower rate than before. That is small comfort when it comes to our household budgets.

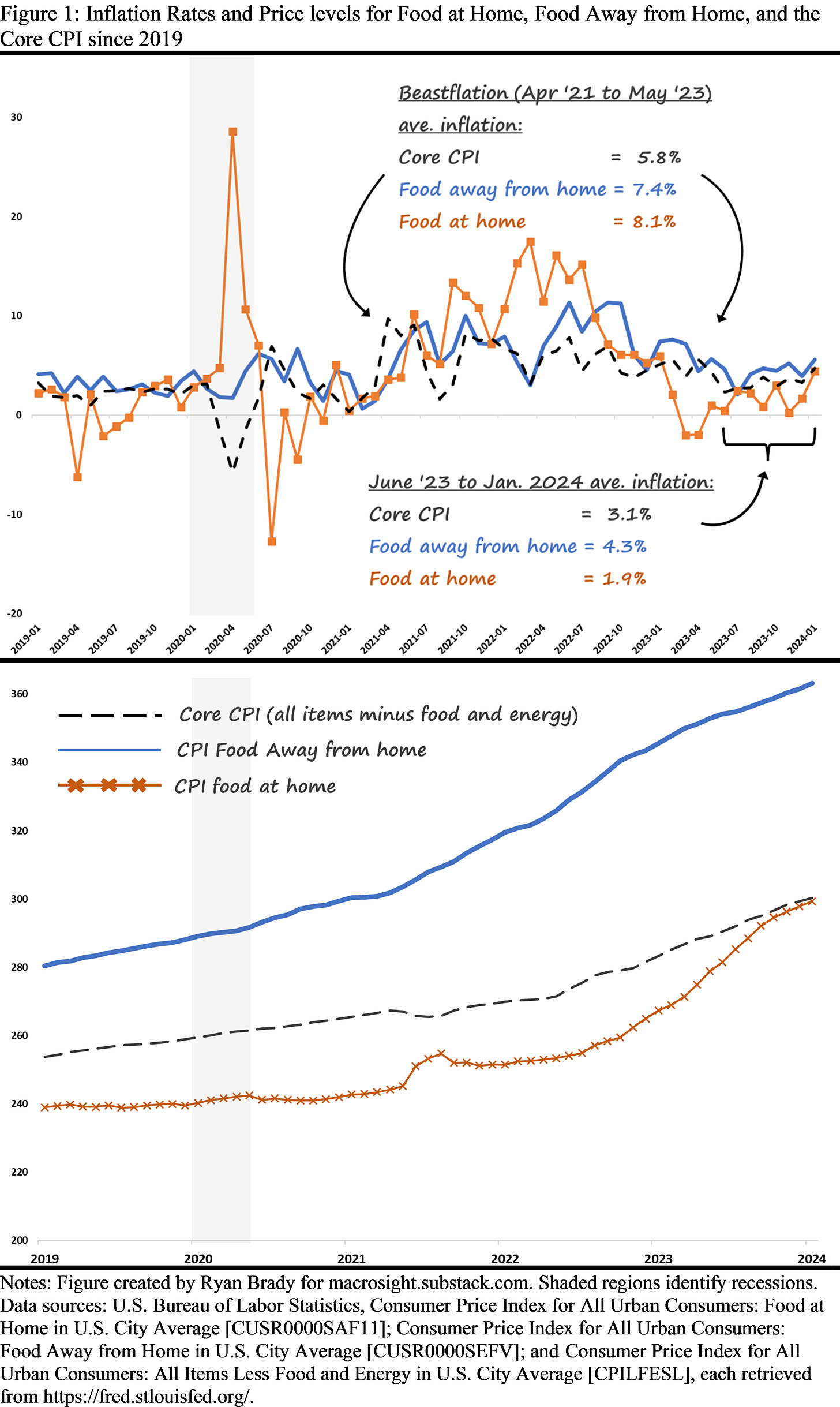

For example, Figure 1 displays the rates of inflation (annualized monthly percent change) and the price levels for the Consumer Price Index for “Food at Home,” the Consumer Price Index for “Food away from Home,” along with the Core Consumer Price Index (which excludes food and energy) since 2019.2 All three indices are published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and represent three of the many versions of the CPI that the BLS puts out (see this Macrosight post for an overview).

The rate of inflation for each index is shown in the top panel, and the price levels for each in the bottom panel. Let’s asses the top panel first.

Figure 1 reveals that the rate of inflation for Food at Home (orange line) is more volatile than the core CPI (the dashed black line) and more volatile than Food Away from Home.

The rate of inflation for Food at Home spiked dramatically during 2020 (reaching 29% in April of 2020). But, the rate also dropped quickly over the next three months (reaching a deflation rate of -13 percent in July of that year).

Food at Home had the highest rate of inflation for the duration of the “Beastflation”3—the period spanning April 2021 through May 2023—peaking at about 18 percent in March 2022. Yet, the rate of inflation for Food Away from Home was not far behind Food at Home during Beastflation.

Since this past summer the rates of the two food CPIs and the core CPI have all come down—that is the disinflation mentioned above.

Disinflation is good news. But, it is the lower panel of Figure 1 that makes comments from the aforementioned CEO really stick in the collective craw.

The bottom panel of Figure 1 displays the index values for the CPI indices. These values represent an average of the prices we are paying for Food at Home, and for Food Away from Home. (Recall, it is from the index levels that we derive the rate of inflation; the rate of inflation is the rate of change of the price level.)

What do the price levels tell us? The price levels capture what we see when we look at our grocery store receipts—every month prices are getting higher and higher.

On the one hand, since June of 2023, the rise in the price level for Food at Home has been “flatter” than Food Away from Home or the Core CPI. That, too, is evident in the top panel where the rate of inflation for Food at Home over the past eight months has averaged 1.9 percent. So perhaps that is at least a sliver of good news? On the other hand, the average cost of Food at Home has risen 21 percent since January 2021!!4

This leads us to the crux of the matter stated at the outset: food prices have been in disinflation for the past few months. But, they are still going up, and have done so by a lot in the past few years.

Why don’t prices fall?

Like anyone whose parents bought Raisin Bran instead of Fruit Loops, it is easy to be disappointed and even angry at the rising food prices evident in Figure 1. This begs the question: Why doesn’t the price level fall for extended periods of time or at all? Notice, for example, the long upward rise of the three indices over decades, as shown in Figure 2.

Clearly prices have been on an upward march for a long time. While there is some slowing of the increase in the Food at Home price level at various points in history—certainly more so than Food Away from Home and the Core CPI—at no point since 1953 has any of the indices displayed a prolonged period of a downward (deflationary) trend.5 Why not?

Inflation Bias

Why won’t prices fall? While a deep dive into answering this is beyond the scope of one blog post, a pithy explanation is the following: we won’t let them fall.

How so? As explained in this Macrosight post, macroeconomists boil inflationary forces down to three big factors—the output gap, expectations and supply shocks. Here I am going to emphasize aspects of the first one, when the output gap is positive (the economy is in an expansion) and when the output gap is negative (the economy is in, or heading into, a recession).

Expansion

When the economy expands beyond potential GDP, prices rise. And while the Fed typically responds to that situation by trying to slow the economy, they may respond too late or with not enough vigor (like in, ahem, 2022). As a result, inflation rises and our price level continues its upward march.

Why might the Fed make such mistakes? Because it is really difficult to properly judge the business cycle and it is not easy deciding to put people out of work. While the Fed does have a method to its decision-making process, policy makers, being human beings, cannot help but have a bias towards inflation. Meaning they are more likely to let prices rise than be too aggressive and risk harming the economy unnecessarily.

To drive the price level down to levels observed in the past would require a very aggressive contractionary policy, one that would likely lead to a severe and potentially long recession. To really squash inflation in late 2021 and 2022, for example, the Fed would have needed to be way more aggressive in raising rates.

Recession

On the flipside, when the economy takes a nose-dive and falls below potential GDP, the Fed reacts quickly and aggressively to lower interest rates and pump money into the economy through its various policy mechanisms. On top of that, the U.S. Congress jumps in with their version of economic stimulus (as discussed in this post).

By propping up spending in the economy during a recession, the combined actions of our federal government keep prices from falling to a degree than they might have otherwise. That does not necessarily imply our policy makers should not respond in that way to a recession; I mean simply that is a consequence of such actions.

Hence, there is an asymmetry to the forces that drive prices up and down over our business cycle. When times are good, we let prices inflate. When times are bad, we move to keep prices from deflating.

That is our Inflation Bias.

Perhaps if one makes millions of dollars a year, the dogged upward rise in the prices one pays at the grocery store would be less of an issue. What an existence that must be. Alas, for the rest of us, I guess it’s a bowl of Apple Jacks for dinner.

Postscript

After reading the above, you might be wondering, “But, the products of some prices fall, right? So, why not food?”

Those are good questions. Yes, the prices of some products do fall over time. Case in point, Figure 3 displays the rate of inflation and price level for Televisions alongside the Core CPI since 1996 (when the BLS first stared publishing the series on televisions).6 (Note: to facilitate the visual comparison, in the bottom panel of Figure 3 the axis for Televisions is on the right and axis for Core CPI on the left).

The price of televisions, like other electronic items such as computers and computer software, have come down appreciably and consistently over time. As annotated in the top panel of Figure 3, the CPI for Televisions from 1996 to 2019 deflated by about -16 percent. Since 2020 that deflation has been comparatively modest at “only” -6.4 percent. This deflation is also evident in the bottom panel of Figure 3, which shows the decline in the price level for televisions over that time period.

As you can probably guess, the rate of technological change in electronics has driven this plunge in prices. This begs the question: why can’t that happen with other items in the Core CPI, or for Food at Home and Food away from Home?

In theory such a drop is possible for any good and service, should technological advance have such a profound effect on the item and the market for that item. Yet, there are countless factors that determine the price of a single good or service. As economists like to say, “it’s supply and demand.”

On the supply-side factors such as the costs of the inputs that go into making the item, how labor-intensive it is to make the item, the transport of the inputs and the item itself, and regulation that impact the production of said item—to name just a few examples—all matter in some way.

On the demand-side, the popularity of the item, whether or not there are alternatives to the item, the stage of the business cycle, competition in the market for that item, whether the item is a “luxury” or a “necessity,” and so on, all affect the price.

Should all of those forces come together in a particular way, then it is possible that any good or service could experience a deflation in its price. In practice, however, what “a particular way” means is that technological change needs to dramatically alter how those forces come together to determine the price of the good or service. This is what we see with televisions and electronics in general. The pace of technological improvements in the production of those items has played an out-sized role in driving down those prices.

For most goods and services we regularly consume, however, that has not been the case. Or, it has not been the case for enough of the 80,000 goods and services that are tracked by the BLS with their various CPI indices.

As explained previously by Macrosight, disinflation means that the inflation rate is positive, but, the positive rate is getting lower and lower over consecutive months. On average prices are still rising, but at a slower rate.

As defined by the BLS Food at Home “refers to the total expenditures for food at grocery stores (or other food stores) and food prepared by the consumer unit on trips. It excludes the purchase of nonfood items.” Food Away from Home “includes all meals (breakfast and brunch, lunch, dinner and snacks and nonalcoholic beverages) including tips at fast food, take-out, delivery, concession stands, buffet and cafeteria, at full-service restaurants, and at vending machines and mobile vendors. Also included are board (including at school), meals as pay, special catered affairs, such as weddings, bar mitzvahs, and confirmations, school lunches, and meals away from home on trips.”

Defined by Macrosight as “The inflation rate is positive, but, the positive rate is increasing rapidly resulting in higher and higher rates of inflation over consecutive months. Generally caused by historically high consumer spending, 5 trillion dollars worth of stimulus money, supply-chain constraints, and the Fed misreading the situation—not necessarily in that order.”

Calculated as follows: Increase = (((Price Level in Jan. ‘24)/(Price Level in Jan. ‘21))-1)*100. The increase for Food Away from Home over the same period has also been 21 percent; and 16 percent for the Core CPI.

During the Great Recession the Food at Home index decline for ten consecutive months, while during 2016 and early 2017 the index fell for 11 consecutive months. Both represent the longest deflations in any of these three series since 1953. The next closest deflation streak was six months, which occurred in 1967.