The Fed, as always, is in the news. This week it was the near-attempted-but-not-really-firing of Jerome Powell, which led to some stock and bond market jitters. The bond market is a particularly important metric for assessing both our government’s fiscal performance and the Fed’s performance.

For the former, the market interest rates on U.S. government debt should increase as investors become more suspicious of the fiscal soundness of Uncle Sam. If I am going to loan money to those holding the purse strings in Washington, D.C., I may very well demand a higher interest as compensation for those holders’ decisions.

For the Fed, the interest rates on long-term government debt also reveal something about the Fed’s performance; as in how financial market participants view that performance.

If I am going to loan my money to the government for a long period of time, I want to be at least partially compensated for future inflation. Otherwise, why bother investing in a long-term bond (when you could put your money in shorter term assets instead)? Hence, if I, and investors in general, change our opinion about future inflation, one should see that “built” into the long rates, meaning long rates rise as a consequence.1

With respect to such future inflation expectations, long rates may increase if investors think the Fed is doing a poor job of keeping inflation in check, Or, long rates may jump if investors anticipate the Fed chairman getting fired and replaced by someone less serious about keeping inflation in check.2

Figure 1 shows a composite of rates on long-term U.S. government bonds (for bonds with a maturity greater than ten years). The measure is generated, and published, by the U.S. Treasury (see here). The figure displays the rate at the daily frequency since the beginning of the year.

The latest reading for this measure was 5.0 percent (as of yesterday, July 17th). While this rate has been trending back up since the beginning of July, its not clear that there was anything unusual going on this week (from Monday of this week to this Thursday, the rate went from 4.95 to 5.0). So perhaps any talk of markets getting skittish about the Jerome Powell-related news was just that, talk?

However, there is a noticeable “break” in the timeline in Figure 1. Up until the beginning of April there was a downward trend. Since the beginning of April, the opposite is true (the timing is not likely a coincidence, of course).

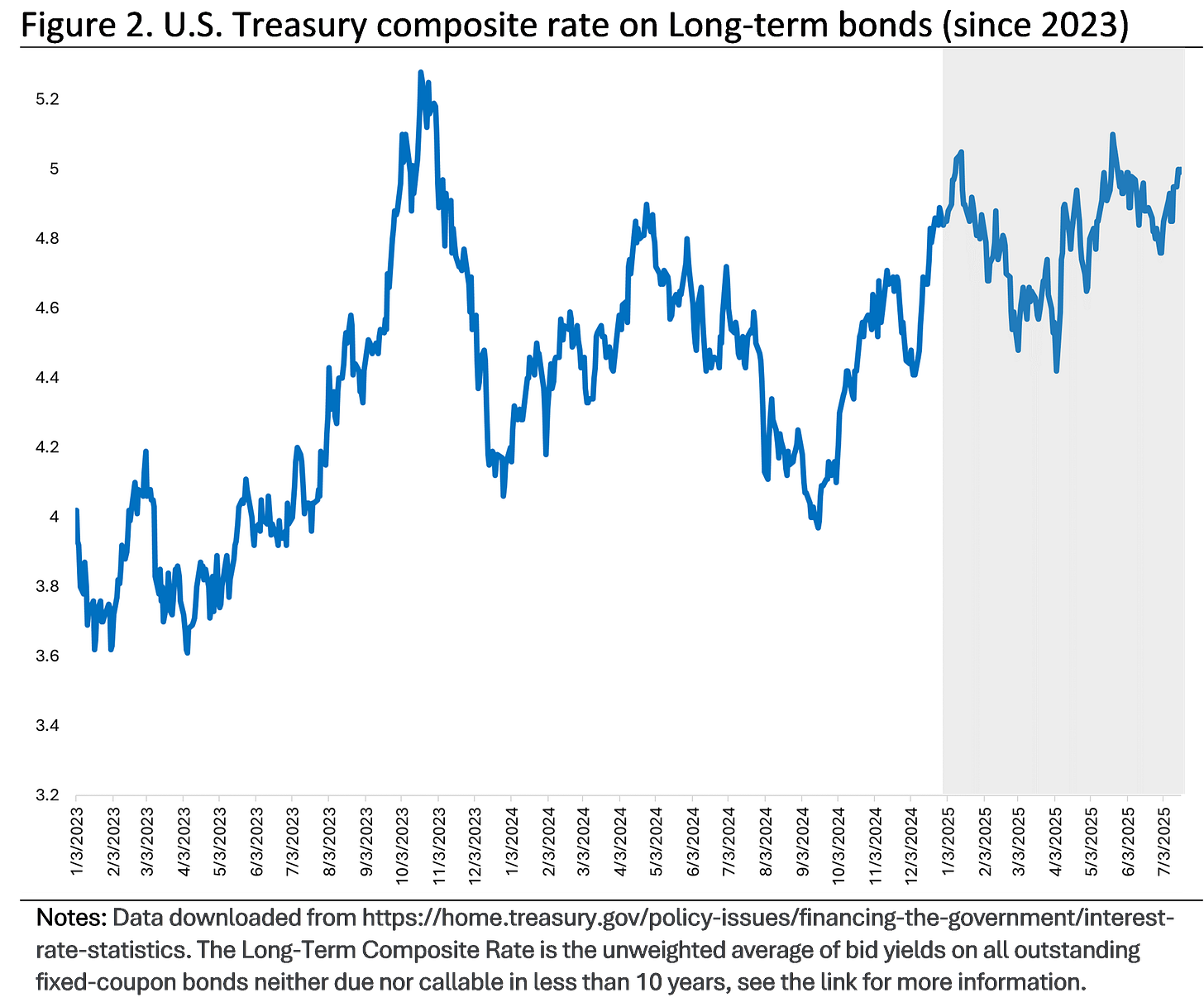

To gain a bit more perspective, let’s look further back. Figure 2 shows this same interest rate data back to the beginning of 2023 (again at the daily frequency). 2025 is shaded in grey.

From this perspective, this measure of long-term bond rates has been trending up since September of last year (right around the time the Fed cut their target interest rate by 50 basis points). Prior to that, the rate had come down (over the first half of 2024). Though if you look at the entire two-and-half-year timeline, this figure reveals an upwards trend since 2023 (obviously there has been a bit of volatility over the time span).

Interestingly, the general increase in this measure of long rates has trended up as the rate of inflation has trended down.3

As is often in the case with economic or financial data, it is difficult to draw any strong conclusions from this measure of long-term interest rates. Perhaps the most succinct is this: long-rates don’t seem to be particularly bothered by very recent political news, yet, the investors driving those long-rates are still bothered enough by something or many things that long rates show little sign of abating.4

We also see this with the 30-year mortgage rate, as explained in the post “The Rising 30-year mortgage rate”.

For the link between the credibility of the Fed and inflation, see these posts Macrosight: “Street Cred” and “The Werewolf Problem”).

The consumer price index peaked in the summer of 2023. See data on that downward trend in the Macrosight post, “Deflation!?”

This conclusion probably deserves a “Gee, thanks for that insight, Captain Obvious” review.