[Note to the reader: Macrosight wrote about U.S. imports and the potential effect of tariffs about a year ago (April 19, 2024, in fact). I am not going to repeat all of that in this post, but I will reference it throughout. Now onto this post . . .]

If this blog has an “analytic” modus operandi, it is the following: in order to understand what is happening now in the economy, and to form expectations for what will happen next in the economy, we need to understand what is “normal” for our economy.

The motivation for that thought process—and this blog for that matter—came from Covid-19 and the abnormal that event wrought on the macroeconomy.1 Now five years on, macroeconomic data has long returned to normal, a point made multiple times in this blog. Well, it seems like here in April 2025, we’re going to get another round of abnormal—this time in the form of a change in our country’s trade policy.

What will happen is obviously uncertain. There are logical guesses or forecasts one can make, and many in the media are obviously making those, but the macroeconomy has a way of surprising us. Either way, in order to have any sense of what may come, we should look at what the “normal” has been.

Import Prices

Figure 1 displays the month-to-month percent changes in the price index for U.S. imports going back to January. This series is produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) along with its litany of price indexes on just about every good and service in our economy. This series, published monthly, tracks the prices of all imported commodities by “end use.”2

While the ups-and-downs of import prices do not provide any sort of “aha” insight, what it is important is the typical growth in this price series. From 2020 through February of this year, the month-to-month change in import prices average about 0.2 percent. On an annualized basis, that comes out to be about 2.9 percent. That is about twice the average rate of increase than observed over the two-decades prior to 2020.3

But, this series can only tell us so much with respect to tariffs. In fact, what is kind of annoying about this series is that the BLS subtracts off any tariffs associated with the imports tracked in this index (instead, this index focuses on the prices “at the port,” before Customs collects the tax). So maybe this price discussion was a big waste of time.4

How about Imports?

Recall that GDP represents every thing bought, sold and produced in our economy. In measuring GDP, the Bureau of Economic Analysis also defines four major GDP-sub-categories within the broader statistic: consumer spending (68 percent of GDP), investment spending (about 17 percent of GDP), government spending (17 percent of GDP) and net exports (a negative 4.5 percent of GDP at the end of 2024).

The latter is equal to exports minus imports,

Net Exports = Exports – Imports

Net Exports—more commonly called the “trade gap”—is typically negative because we consume more foreign goods than foreigners consume from us. This has been the normal state of affairs for decades (see Figure 1 in this post). The last time the trade gap was positive, believe or not, was in 1991. And even then it barely got above zero. Since then the average trade gap has been about -2.7 percent.

But, just because Net Exports makes up the smallest share of the four GDP categories, does not mean the dollar values associated with imports or exports are small. At the end of 2024, U.S. imports totaled $3.7 trillion and exports equaled $2.6 trillion (both numbers represent 2017 constant or inflation-adjusted dollars).

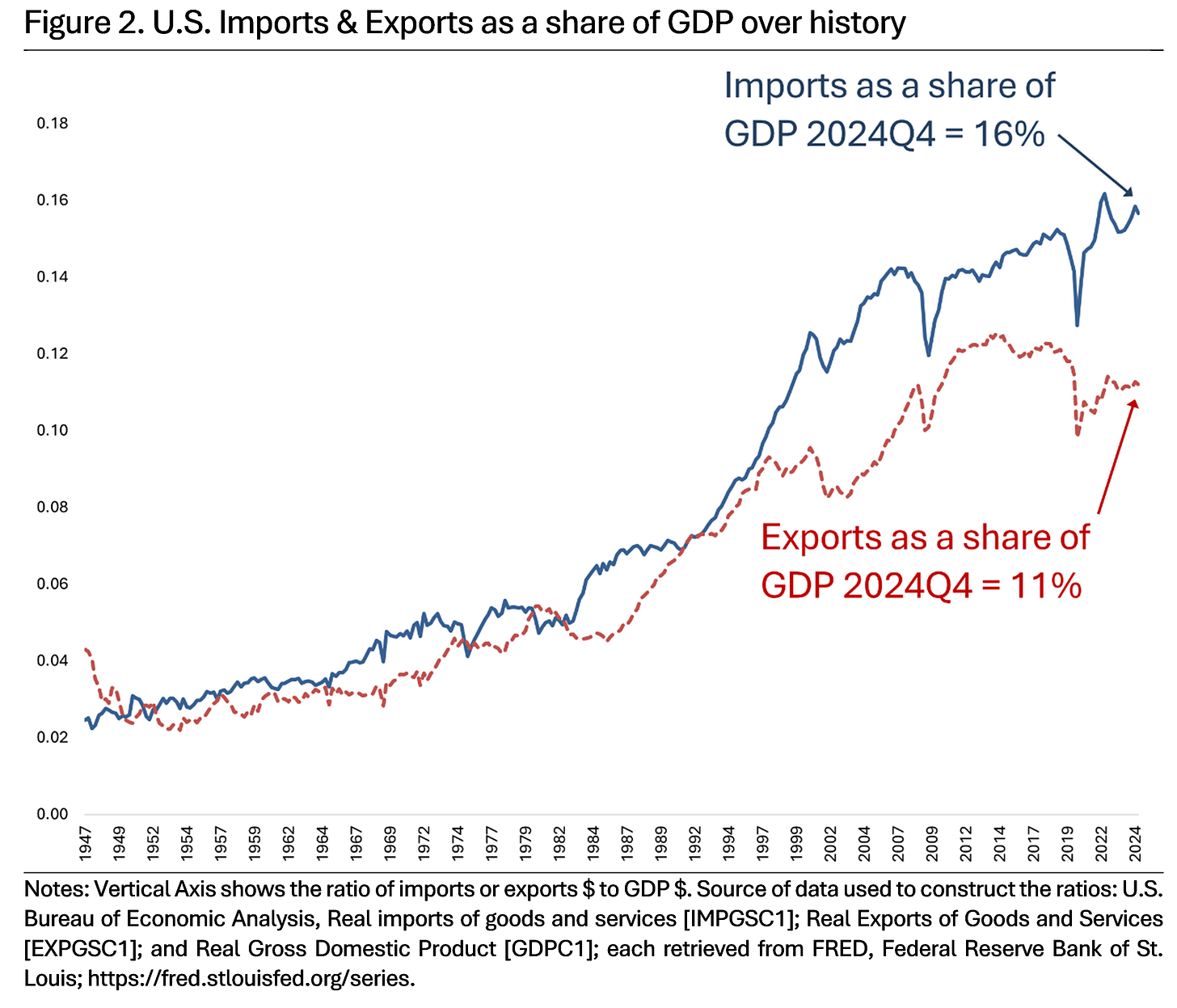

Figure 2 displays those dollar values in terms of the shares of U.S. imports and U.S. exports relative to GDP.

The share of U.S. Imports to GDP at the end of 2024, for example, equaled 16 percent ($3.7 trillion of imports divided by the value of real GDP at the end of 2024, $23.5 trillion (inflation-adjusted dollars)). And, as you can see on the figure, exports were about 11 percent of GDP.

The effect of tariffs on Net Exports & GDP

In general, it is challenging to assess using macroeconomic data exactly how new tariffs effect the trade gap or GDP (I discussed this towards the end of this post). But here are some things to keep in mind:

With respect to the new tariff policy the Trump administration just enacted, it is easy to speculate that in the near-term imports will fall, exports will also decline, and GDP, too, will decline.

But, the latter may not decline as a direct result of a change in the trade gap. What happens to the trade gap all depends on how much imports change relative to how much exports change. With so many new tariffs imposed by the United States and other countries, it is almost impossible to say at this point how the total value of Net Exports (the trade gap) will change.

If GDP declines, it will probably be due to uncertainty or fear surrounding the new policy. In the least, that uncertainty and fear appears to be manifesting in the stock market this week.

The effect on the trade gap in the long run is also uncertain; yet, based on historical experience across time and countries, is relatively easy to predict. If tariffs make trading across borders more expensive then it stands to reason the absolute value of the trade gap will become smaller, and the shares of imports and exports will decline.

The effect on GDP in the long run—on our economic growth—is probably negative. Again, the historical evidence, across multiple countries and decades, reveals that when countries restrict trade, their economy suffers. That is not to say GDP growth takes a nose-dive over the next few years. Rather, it may not grow as fast as might otherwise with more liberal trade policy.

But, that U.S. trade policy has become less “open” is not necessarily a new thing. As pointed out by journalist Fareed Zakaria, this has been the case under both President Trump (first term) and President Biden. How has that mattered for GDP growth? Well, since 2017 quarterly inflation-adjusted GDP growth has averaged 2.6 percent (annualized). From 1993—the beginning of the modern era of open borders, I would say—through 2016, GDP growth averaged . . . 2.5 percent.

Finally, it is possible that economic growth could be enhanced by these changes. How that manifests is unclear, but it would probably be through some mechanism related to technological change. If, for example, U.S. companies are able to harness AI-related technology to enhance their existing factories, or the future factories they are now incentivized to build, that would boost productivity, which would then boost economic growth.

To end on a hopeful note, the U.S. economy has proven to be resilient in the face of many a negative “shock,” just in the last 25 years alone. Whether financial panics, economic policies, or pandemics, the U.S. economy has managed to overcome and outlast what seemed ruinous at the time. Macrosight’s best guess is that it will outlast this one as well.

Actually, that “process” is the basic strategy of any forecasting effort. The best forecast is based on historical patterns in the data. Then, one posits different “scenarios” that may cause that pattern to deviate from the historical “normal.” Macrosight describes basic forecasting methodology here.

The BLS is not explicit by what “end use” means (though they do provide detailed information on the price indices here). However, typically in economics, that refers to how a product or commodity is ultimately used. This could be for final consumption by households, as an input in the production of other goods and services, or for capital investment (e.g., equipment or machinery used by a company to make other things).

It is also normal for import prices to be volatile (as discussed in the aforementioned previous Macrosight post on this topic). The volatility of this series as measured by the standard deviation has been a little less over 2020 to 2025 than in the 2000 to 2019 span—11.4 percent to 16 percent, respectively (on an annualized basis).

Ending that section with “this doesn’t tell us much” is similar to me telling my students, after a 50-minute lecture, “but all of that content actually won’t be on next week’s exam.” Teaching tip: never tell them that at the beginning of the class.